empty of future, renew the sign: lucent paradox, ineluctable trace ...

31.12.06

ludwig & the death masque of shagspear

Marie Antoinette walks under trees, across brown dry curled up autumn leaves, towards the Palace of Versailles. We don't know what year it is, only that it was before 1793. It's not her fault, any more than her Hapsburg nose; but when we go close on the leaves we find they are actually dry curled up bodies of men & women incinerated in some historical catastrophe or other. We don't know what year it was, only that it is after 1793. Exactly 54 years later an indigent painter, having given up his job at the court of the archduke in order to nurse his sick half brother, Karl, buys in a second hand shop in Mainz a picture of a poet on his death bed, wearing laurels, with a tall thin candle burning by the bedstead. The small painting, oil on linen, is in a kind of fold-up wallet & bears the caption: Shakespeare. And a date, 1637. The painter, distraught at the languishing of his brother, from typhoid, becomes obsessed with the painting; he believes it is after an earlier work with the same subject, or perhaps even from a death mask. When he learns that there was, in the same collection that the painting came from, a plaster head, he begins a search for it in the antique & second hand shops of Mainz. Two years later, in the shop of man named Wilz, he finds it, buried under rags and other surplus stuff, & very dirty. He believes this to be the death mask of Shakespeare, as well as the inspiration for the painting. There is a date on the back, 1616. He thinks it will make his fortune. He takes the cast to England, where another half brother, Ernst, has been appointed the intimate companion & secretary to Prince Albert. The death mask of Shakespeare is celebrated in London, it is even exhibited at the British Museum; but since no-one can work out how it came to be in Germany in the first place, it is not authenticated & no-one, not even the Museum, will pay the 5000 pounds he wants for it. The painter, also a naturalist, attends a scientific conference in Edinburgh & travels in the Highlands. Later, his friend & patron, the zoologist Kaup, lends him the money to go to the Antipodes. He sails via Rio de Janeiro to Van Diemens Land, where he is valued for his skills at conversation & his expertise in the arts & sciences. After the gold rush he goes to Victoria, prospecting on the Bendigo fields & finding there enough gold to repay Kaup. Later he joins high society in Melbourne, & later still is appointed official artist on an Expedition of Discovery into the Interior, during which, persecuted by the Irish policeman who leads the party, he dies, aged fifty-two; though not before executing some luminous watercolours that still seem to tell of a world hithertofore unapprehended. In December the same year (1861) Prince Albert also dies & the indigent painter's half brother Ernst, lacking employment, returns to Germany, as does Shakespeare's death mask. It will be another hundred and fifty years before anyone dares authenticate it & even then there will be skeptics; by which time it will be known that the small oil painting shows, not Shakespeare, but Ben Jonson on his death bed. Meanwhile, Marie Antoinette moves slowly towards the palace, her delicate shoes crunching over the corpses of leaves, unconcerned, indeed oblivious, as to whether she is walking into or out of history.

16.12.06

The (Un)Imaginable Future

for SKR

1. Baboon, we have travelled far ...

Look closely at a human embryo within a womb & you will find a cloud of retroviruses swarming the placenta, the remnants of an ancient infection. Without viruses, we might still be laying eggs. For protection, a single layer of an embryo's cells merges into a continuous barrier, a syncytium. Where embryologists spotted spheroid retroviruses budding from cells in a baboon placenta, 30 years ago. A viral gene was making a protein, syncytin, that caused human placental cells to fuse. An artificial molecule, a morpholino, prevented embryos from making the cell fusing proteins. Most inherited viruses are muffled versions of the original infectious forms. The missing viruses vanished when the inherited forms prevented reproduction within the host. HIV may finally be conquered by ancient biological means. It could even lead to a new human species. These few nonprogressors could go on to form the new species. We have the capacity to prevent it being an evolutionary event for the first time.

2. Refugia

Europe is off the hook. The North Atlantic Ocean system ferrying warm water northwards from the tropics is not about to shut down. The warm interglacial period that began when the Ice Age started to wane 17,000 years ago is nearly at an end. Plant & animal species can survive trying times by retreating to safe havens or refugia—places as small as a sheltered valley or a mountain top. Phylogeographers work from both ends—past & present—to determine what species might do in the future. Refugia were the source of colonisation by plants & animals after the Ice Age. The world’s deserts, from Africa & Asia to Australia, have been virtually ignored. In the wet tropics, the climatic & biological requirements of many different species have been determined, & where they held out in the past. The secret is to combine paleo data with genetic information about living species.

3. The Return of the Trees

Forests are increasing across the world after centuries of being destroyed. The increase is most rapid in Spain & the Ukraine, the decrease quickest in Nigeria & the Philippines. The great gains are in China & the United States. Brazil & Indonesia are losing the most. This great reversal could stop the styling of Skinhead Earth & by 2050, expand global forests by 10% or 300 million hectares, the area of India. Where forest coverage is stable. Forests expanded in Europe after the Black Death & diminished again in the Age of Exploration. French forestry records dating back to the Middle Ages show an arboreal renaissance unaffected by population increases. Wealth is an indicator in reversing deforestation. All countries with a GDP per capita higher than Chile’s ($US4600.00) have increased their forest cover since 1990. Replanting in China offsets Brazil’s annual loss of 3.1 million hectares. Indonesia felled a vast area of forest but harvested less timber than the US, which gained growing stock. The main danger to forests is fast-growing, poor populations who burn wood to cook, sell timber for cash & fell trees to plant crops. Harvesting biomass for fuel forestalls the restoration of land to nature.

4. Archaeology of the Brain

Above ground testing of nuclear bombs between 1955 & 1963 led to a big increase of radioactive carbon-14 in the atmosphere around the globe. Levels have since tapered off as the carbon-14 was absorbed by the oceans, plants & animals. A person born in 1963 has twice as much carbon-14 in their system as someone born in 1999. This carbon-14 bomb spike provides a unique opportunity to date human tissue. Carbon-14 levels in the DNA of cells reflect atmospheric levels at the time the cells were born. Levels in the neurons from all areas of the cerebral cortex are as high as the atmospheric levels at the time of each individual’s birth. Neurons of the cerebral cortex are thus the ones you were born with. We don’t make new neurons in this decision making region of the brain. Having a permanent population of cells that store information about language, maths & logic over a lifetime may be better than growing new naïve cells that have not been exposed to years of experience, as is the case with fish & frogs. Human muscle cells are fifteen years old, bone, ten years, liver, two, red blood cells, 120 days, outer skin layer, two weeks, gut lining cells, five days; unlike your hippocampus, which regenerates, your front brain is the same age as you are.

Baboon ... adapted from: The Australian, 1.11.06;

Refugia adapted from: The Australian, 8.11.06;

The Return of the Trees adapted from: The Australian, 22.11.06;

Archaeology of the Brain adapted from: The Sydney Morning Herald, 14.12.06.

1. Baboon, we have travelled far ...

Look closely at a human embryo within a womb & you will find a cloud of retroviruses swarming the placenta, the remnants of an ancient infection. Without viruses, we might still be laying eggs. For protection, a single layer of an embryo's cells merges into a continuous barrier, a syncytium. Where embryologists spotted spheroid retroviruses budding from cells in a baboon placenta, 30 years ago. A viral gene was making a protein, syncytin, that caused human placental cells to fuse. An artificial molecule, a morpholino, prevented embryos from making the cell fusing proteins. Most inherited viruses are muffled versions of the original infectious forms. The missing viruses vanished when the inherited forms prevented reproduction within the host. HIV may finally be conquered by ancient biological means. It could even lead to a new human species. These few nonprogressors could go on to form the new species. We have the capacity to prevent it being an evolutionary event for the first time.

2. Refugia

Europe is off the hook. The North Atlantic Ocean system ferrying warm water northwards from the tropics is not about to shut down. The warm interglacial period that began when the Ice Age started to wane 17,000 years ago is nearly at an end. Plant & animal species can survive trying times by retreating to safe havens or refugia—places as small as a sheltered valley or a mountain top. Phylogeographers work from both ends—past & present—to determine what species might do in the future. Refugia were the source of colonisation by plants & animals after the Ice Age. The world’s deserts, from Africa & Asia to Australia, have been virtually ignored. In the wet tropics, the climatic & biological requirements of many different species have been determined, & where they held out in the past. The secret is to combine paleo data with genetic information about living species.

3. The Return of the Trees

Forests are increasing across the world after centuries of being destroyed. The increase is most rapid in Spain & the Ukraine, the decrease quickest in Nigeria & the Philippines. The great gains are in China & the United States. Brazil & Indonesia are losing the most. This great reversal could stop the styling of Skinhead Earth & by 2050, expand global forests by 10% or 300 million hectares, the area of India. Where forest coverage is stable. Forests expanded in Europe after the Black Death & diminished again in the Age of Exploration. French forestry records dating back to the Middle Ages show an arboreal renaissance unaffected by population increases. Wealth is an indicator in reversing deforestation. All countries with a GDP per capita higher than Chile’s ($US4600.00) have increased their forest cover since 1990. Replanting in China offsets Brazil’s annual loss of 3.1 million hectares. Indonesia felled a vast area of forest but harvested less timber than the US, which gained growing stock. The main danger to forests is fast-growing, poor populations who burn wood to cook, sell timber for cash & fell trees to plant crops. Harvesting biomass for fuel forestalls the restoration of land to nature.

4. Archaeology of the Brain

Above ground testing of nuclear bombs between 1955 & 1963 led to a big increase of radioactive carbon-14 in the atmosphere around the globe. Levels have since tapered off as the carbon-14 was absorbed by the oceans, plants & animals. A person born in 1963 has twice as much carbon-14 in their system as someone born in 1999. This carbon-14 bomb spike provides a unique opportunity to date human tissue. Carbon-14 levels in the DNA of cells reflect atmospheric levels at the time the cells were born. Levels in the neurons from all areas of the cerebral cortex are as high as the atmospheric levels at the time of each individual’s birth. Neurons of the cerebral cortex are thus the ones you were born with. We don’t make new neurons in this decision making region of the brain. Having a permanent population of cells that store information about language, maths & logic over a lifetime may be better than growing new naïve cells that have not been exposed to years of experience, as is the case with fish & frogs. Human muscle cells are fifteen years old, bone, ten years, liver, two, red blood cells, 120 days, outer skin layer, two weeks, gut lining cells, five days; unlike your hippocampus, which regenerates, your front brain is the same age as you are.

Baboon ... adapted from: The Australian, 1.11.06;

Refugia adapted from: The Australian, 8.11.06;

The Return of the Trees adapted from: The Australian, 22.11.06;

Archaeology of the Brain adapted from: The Sydney Morning Herald, 14.12.06.

11.12.06

every cloud ...

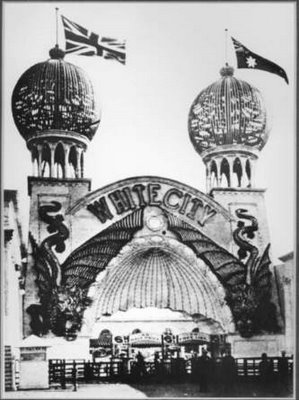

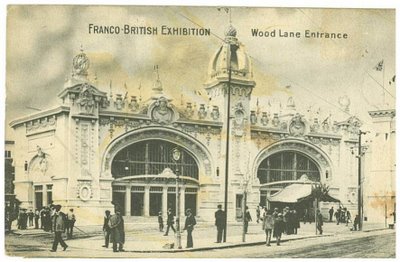

Just heard from AUP that they will publish a collection of shorter pieces of mine, under the title Waimarino County, in May next year. This is the image I'd like to see on the cover:

It's maybe not clear, but that's a photo taken from one stage coach of another, further on down the Tohunga Road on the south-western slopes of Ruapehu, the mountain you can see above the bushline ahead. I grew up not far away from here, to the left of the picture as you look at it, in the 1950s ... but this image is from the early 1900s, about a century ago from now.

It's maybe not clear, but that's a photo taken from one stage coach of another, further on down the Tohunga Road on the south-western slopes of Ruapehu, the mountain you can see above the bushline ahead. I grew up not far away from here, to the left of the picture as you look at it, in the 1950s ... but this image is from the early 1900s, about a century ago from now.

7.12.06

Exeunt

After

the fire, the long ice. Antic clashing among the shadowy rocks. At the beginning, before what would be. After the ice, water. Abracadabras of flannel flowers, doves erupting from the sleeve of god. Apples of Sodom. Arrival of the always that went everywhere. Après le déluge … a forgetting, a wandering wondering where are the true states of mind. Among the myriad that we pass through, or that pass through us, each minute, hour, day, which are real? Areal?

All

Before

forgetting is remembering. Before remembering, mind. Before mind … god? Bruised beyond redemption, broken in pity, biblical. Besotted, fearful, today you remember everything. Bountiful memory! Bright lie! Begin at the beginning and go all the way to the end that has not yet come. Bolder than bold, blacker than black, botched or not, the whole kit and caboodle stretches out before and behind you. Both the track and the tears; both landscape and inscape.

Blessed

Could

it be so? Child of god, where do you wonder? Can you say or is it a conundrum without issue? Cordillera in the consciousness, cliffs of fall, concussive recitative … let us wander the shores of unknown seas. Cross into the beyond of yesterday, that future lost forever in the past. Criminal, coeval, conspiratorial, caught. Carelessly scattering the vowels and consonants that hithertofore we have clung to, or exchanged. Clouds of unknowing call us.

Come

Damnation

is the fate of those who abandon god. Does the same apply to we who have been abandoned by god? Do you know the answer to this riddle, strange traveller? Dolce et decorum est pro patria mori. Don’t forget: the last refuge of a scoundrel. Days and nights in the wilderness. Daguerreotypes of ghosts never before seen, never seen again. Down is the name of a country we cannot live in or leave. Delights of paradise whispered in the ears of the damned.

Demon

Eidola

mass at the doors of perception. Endlessly suggestive of that which might have been, might yet be. Eidetic, erogenous, never less than weird. Except that … who can say what form a phantom or a spectre might take when seen from the other side of forever? Eye of god, inhuman, pitiless, empty of sentiment, stark as the last sunlight on Girdlestone peak … execrable. Exiting that gaze into the malign uncertainties of our own, they persuade us of the existence of angels.

Eon

First

there was nothing. Finally, nothing again. From then to now to when, what? Fandangos of god’s superlative elegance, or the finangling of demons? Fricassees of atomic moles, genetic soup, hollow cell membranes frozen inside meteors dropping into Canadian lakes. Fur flies in the north. Fivestones. Fissile material. From the far reaches, a murmur of voices, cosmic weeping at the margins of the black forest, the black ocean, the black sky. For what did we come? For why?

Fall

God

’s blood runs in your veins. God’s wounds are your wounds. God’s gonads too. Gnomon of the inarticulate sun, guide of the lost, globule of the death star. Given that these are your words, is this then your world? Going towards followed by coming away from. Ground of meaning turned over to an archaeology of exchange in which the other is always substituted for the one. Gloss of an expunged text, grisaille of infinity, cadaver of the perfected body.

Gone

Hell

is the absence of god. Here and now, you suffer all possible torments. Hush-a-bye baby on the tree top. Hoarstones trouble your sleep, the nightmare shrieks down the alleys of your mind. Hope there is in both hopeful and hopeless. Happiness cannot be pursued, not any longer. However it comes, that is how it will go. Higher than light, into the hypnagogia, that sphere beyond spheres, your haploid self ascends. Head in hand, hand to heart, heart in mouth, mouthing.

Horror

Ion

accused of unspeakable acts in the forum, sent into exile. Ithyphallic god of nomads at the edge of the Imperium. Isinglass, mica, finings, glue. In this wine we drown, by this ivy we are strangled, on this isthmus we shall forever stray. Irrefragable, the doom written in the irade: I do not wish ever to hear his name again. In that moment, a chorus of sighs rose from all around, the voices of stones saying over and over again the one impossible word, incunabula of his loss.

Incest

Jah

lives. Jesters unique as kings, one for each. Joking aside, there is no other way of understanding the loneliness of regency. Journeying, sharing the jeroboam, the fool and the monarch shudder to an alcoholic halt under jacinth skies. Jimson weed sends you blind. Jiving with Jesus sends you … just a closer walk with thee … through this world mysterious and vague … Juxtapose half of six billion with their other halves, what do you get? … juvenescence of the year/Came Christ the tiger.

Joy

Kilter

was something he was always out of, in the same way that he was never kempt. Kissed the Blarney Stone, lying on his back and stretching out over the void to place his lips where god could not reach them. Knew that he would never be lost for words again. Keening. Killing him softly with their song. Kurdaitcha man came one night, stole a kidney, since then, the other has been working overtime. K.O. is O.K. backwards. Kilometres to go before we sleep.

Key

Love

late walking in the aisles of rain. Light of evening, Lissadell. Lissom, lubricious, licit … lost. Limbo of libido, Limpopo of lust exiled to the dead heart, limit of thought, god’s lying end. Landloper’s song fades past Tungsten Gate where Xanthe waits no more at the caravanserai. Loveless, lovelorn, lovesick, yet still you love. Lustra pass. Luteous years, tawny with longing. Later, after the rain and the tears and the night’s white sighs, you learn again how to listen.

Loam

Meandrine

paths, through coral, through mind, winding. My god, my god, why hast though forsaken me? Meaning does not inhere. Memory wastes. Materiality fades in the face of the monstrance. Moon, moraine, monosyncline, monsoon. Make of this what you can, for it is certain that you will (l)anguish without protection once god has died. Moreover, he dies again each time he is denied. Mons veneris, unclimbable. Mourning. Miracle is not to have been born at all.

Mystery

Nuncios

reflect upon diplomatic slights, remembered for centuries. Nuncupate wills bequeath only resentment. No-one knows how to end the blood feud between god and the gods. Nor even God himself … not love that I’m running from, just the heartache I know will come. Nepenthes priced beyond your range, nates of loss, neuralgia of the wizened hand. Never again, never before, never more, never never. Nymph in thy orisons … Now anticipates next, next recalls last.

Nectar

Opium

of the masses, law of the discarded middle, oxygen of love, orisons, torsions … O.K. means orl korrect (joc.). On the far side of the ocean, a chemical sea, washing the ferrous sand with its salts. Oleaginous life, clinging to the margins. O western wind, when wilt thou blow? Omphalos. Omit no time. Oligocene to now, epoch of the primates. Opus terminus of the god of all this … order. Or chaos, whichever you prefer. Orb and oblate of the orient. Enceinte.

Old

Primate

of all England, a monkey in robes, wearing a mitre. Primordial delusion, priapic vanity, primum mobile. Perhaps it is time to leave the gods to their own devices, perhaps god’s away on business. Pulsars at the furthest edge of the universe engage his attention. Persuasion will do no good, prayer is useless, promises will not be kept. Puer aeternis in a gavotte with a senescent priest. Pinions engage the clockwork of creation. Plangent, placid, all but played out.

Pluto

Quean

of the imaginary, quatorzain of love, quaternary delusion. Quite why we are here nobody really knows. Quantity or quality remains an incommensurable choice. Quavery voice of the aeons proclaims the eternal recurrence of all things. Questions without answers, answers without questions. Quandary: quarks quark, queers queer, quid or quiddity, who knows? Qur’an is god’s last book? Quiet of evening, stillness of water, faint braille of stars on black quilt of sky.

Quill

Recent

retreats of ice recall earlier epochs, a watery world. Radio love broadcasts on all frequencies, without ratiocination. Railways run to the end of the earth, a train leaves the last platform and climbs into the sky. Round the rugged rocks the ragged rascals … three, three the rivals. Rapturing in a ratskeller. Raucous birds calling from the future, the one god will not see. Reptiles wore feathers in the Jurassic, a rubefaction of time. Rehearsal for undermining, catastrophic reprise.

Rain

Snake

in the garden, saying: Ye shall not surely die. Seismic shift, shatter of bones, eyes opening on the unseen. Saying: Seek and ye shall find. Serein, falling from a cloudless sky, at evening. Saraband or serenade, swansdown of sublunary light, skin sere like old leather. Shofar sounds on the baked plains of Jericho, walls do not fall. Sheer drop, shot silk, satin and lace. Seductive world, how not to eat of god’s apple? Sea pink, sea kale, sea angel, sea horse. Silver and gold.

Song

Triage

of gods, who shall we examine first? Take which fiction to task? Tragacanth for the holy spirit will come, by tumbrel, from the west. Twice told tales of fathers and sons. Tryst or triste? Tomb of reality, trapeze without net, machine without a ghost: this Universe. Tuberous spring, tubercular summer, tumult of autumn, winter of total war. Tessera to enter the Coliseum, where tranced men and beasts contend. Tertian fever. Trumpery of a tired theology.

Time

Umbelliferous

dark. Understanding nothing but, yes, standing under the stars. Unreal City, the capital of Ultima Thule. Unmarked trams spark through the murk, rendezvousing with the Underground at Central. Until you have been unsexed you will not know god’s uttermost ecstasy. Utopia the last stop on the suburban line. Uvular speech. Usurious, uxorious, useless man. Undine spoke last of all, what she said made no sense to anyone not already a water nymph.

Urn

Venusian

inspection of Earth discloses conditions inimical to life as they know it. Verglas clogs in their lungs. Viruses insinuate themselves into their DNA, visiting the future by proxy. Vaster than empires and more slow. Voluptuous time, veridical miracle. Vomer broken by a blow to the face. Vulgarity of blood on god’s lips. Vatic speech interrupted in the forum by an irruption of Goths, Huns, Vandals. Vulcanized rubber on wheels of carts trundling towards eternity.

Vulva

Windows

glazed with yellow light on god’s last afternoon in the world. Worth every minute, it was. Wandered into the Wendy house, looking for laughter. Wasn’t there. When, when and whenever death closes our eyelids … We cannot say why, nor can we stop asking. Wolfram mined in dark valleys, welded to make the adamantine gates, out in the autonomous zone. Whirled beyond the stars, wreathed in sorrow, wrecked. Wraiths at his wittering lips, awaiting the end.

Wind

Xanthe

heartless, unfaithful, beautiful, where did you go? Xoanon of some mysterious god, fallen from heaven, worshipped by barbarians, why? X marks the spot where I wept for you, the yellow acids of the earth staining my skin. Xenophobes gather under the portico, announcing my exile. X rays of my heart show a blackened core, drier than dust. Xeroxs of you proliferate everywhere I go, copies of copies of copies, each generation a little more blurred than the last.

Xylem

Yare

yare, good Iras; quick. Ytterbium or yttrium? You cannot say where in the lanthanides this silvery or greyish metal occurs. Years later, we come again to the yarborough where no number over nine is admitted. Yardbirds rehearse their back and forth, endlessly. Youth is wasted on the young; yet how could it be otherwise? Yawing of a yacht from its course; yaws, passed venereally, colouring the skin red. Yes, anticipate the godly light. Y chromosome, yearning for an X.

Yield

Zac

tanner, a sixpence for her shoe ... Zener cards prove that intuition exists, zig-zagging through consciousness like an unused road. Zenith of possibility, zen of nullity, immured in the zenana. Zodiacal light in the east, tall triangle, after sunset. Zircon nights we danced heedlessly away, in another time, before we lost each other unaccountably and forever. Zygote of the single flight, zeroth of love, gamin inexistent and desired as god, unzip my chest and so remove my heart.

Zero

After

the fire, the long ice. Antic clashing among the shadowy rocks. At the beginning, before what would be. After the ice, water. Abracadabras of flannel flowers, doves erupting from the sleeve of god. Apples of Sodom. Arrival of the always that went everywhere. Après le déluge … a forgetting, a wandering wondering where are the true states of mind. Among the myriad that we pass through, or that pass through us, each minute, hour, day, which are real? Areal?

All

Before

forgetting is remembering. Before remembering, mind. Before mind … god? Bruised beyond redemption, broken in pity, biblical. Besotted, fearful, today you remember everything. Bountiful memory! Bright lie! Begin at the beginning and go all the way to the end that has not yet come. Bolder than bold, blacker than black, botched or not, the whole kit and caboodle stretches out before and behind you. Both the track and the tears; both landscape and inscape.

Blessed

Could

it be so? Child of god, where do you wonder? Can you say or is it a conundrum without issue? Cordillera in the consciousness, cliffs of fall, concussive recitative … let us wander the shores of unknown seas. Cross into the beyond of yesterday, that future lost forever in the past. Criminal, coeval, conspiratorial, caught. Carelessly scattering the vowels and consonants that hithertofore we have clung to, or exchanged. Clouds of unknowing call us.

Come

Damnation

is the fate of those who abandon god. Does the same apply to we who have been abandoned by god? Do you know the answer to this riddle, strange traveller? Dolce et decorum est pro patria mori. Don’t forget: the last refuge of a scoundrel. Days and nights in the wilderness. Daguerreotypes of ghosts never before seen, never seen again. Down is the name of a country we cannot live in or leave. Delights of paradise whispered in the ears of the damned.

Demon

Eidola

mass at the doors of perception. Endlessly suggestive of that which might have been, might yet be. Eidetic, erogenous, never less than weird. Except that … who can say what form a phantom or a spectre might take when seen from the other side of forever? Eye of god, inhuman, pitiless, empty of sentiment, stark as the last sunlight on Girdlestone peak … execrable. Exiting that gaze into the malign uncertainties of our own, they persuade us of the existence of angels.

Eon

First

there was nothing. Finally, nothing again. From then to now to when, what? Fandangos of god’s superlative elegance, or the finangling of demons? Fricassees of atomic moles, genetic soup, hollow cell membranes frozen inside meteors dropping into Canadian lakes. Fur flies in the north. Fivestones. Fissile material. From the far reaches, a murmur of voices, cosmic weeping at the margins of the black forest, the black ocean, the black sky. For what did we come? For why?

Fall

God

’s blood runs in your veins. God’s wounds are your wounds. God’s gonads too. Gnomon of the inarticulate sun, guide of the lost, globule of the death star. Given that these are your words, is this then your world? Going towards followed by coming away from. Ground of meaning turned over to an archaeology of exchange in which the other is always substituted for the one. Gloss of an expunged text, grisaille of infinity, cadaver of the perfected body.

Gone

Hell

is the absence of god. Here and now, you suffer all possible torments. Hush-a-bye baby on the tree top. Hoarstones trouble your sleep, the nightmare shrieks down the alleys of your mind. Hope there is in both hopeful and hopeless. Happiness cannot be pursued, not any longer. However it comes, that is how it will go. Higher than light, into the hypnagogia, that sphere beyond spheres, your haploid self ascends. Head in hand, hand to heart, heart in mouth, mouthing.

Horror

Ion

accused of unspeakable acts in the forum, sent into exile. Ithyphallic god of nomads at the edge of the Imperium. Isinglass, mica, finings, glue. In this wine we drown, by this ivy we are strangled, on this isthmus we shall forever stray. Irrefragable, the doom written in the irade: I do not wish ever to hear his name again. In that moment, a chorus of sighs rose from all around, the voices of stones saying over and over again the one impossible word, incunabula of his loss.

Incest

Jah

lives. Jesters unique as kings, one for each. Joking aside, there is no other way of understanding the loneliness of regency. Journeying, sharing the jeroboam, the fool and the monarch shudder to an alcoholic halt under jacinth skies. Jimson weed sends you blind. Jiving with Jesus sends you … just a closer walk with thee … through this world mysterious and vague … Juxtapose half of six billion with their other halves, what do you get? … juvenescence of the year/Came Christ the tiger.

Joy

Kilter

was something he was always out of, in the same way that he was never kempt. Kissed the Blarney Stone, lying on his back and stretching out over the void to place his lips where god could not reach them. Knew that he would never be lost for words again. Keening. Killing him softly with their song. Kurdaitcha man came one night, stole a kidney, since then, the other has been working overtime. K.O. is O.K. backwards. Kilometres to go before we sleep.

Key

Love

late walking in the aisles of rain. Light of evening, Lissadell. Lissom, lubricious, licit … lost. Limbo of libido, Limpopo of lust exiled to the dead heart, limit of thought, god’s lying end. Landloper’s song fades past Tungsten Gate where Xanthe waits no more at the caravanserai. Loveless, lovelorn, lovesick, yet still you love. Lustra pass. Luteous years, tawny with longing. Later, after the rain and the tears and the night’s white sighs, you learn again how to listen.

Loam

Meandrine

paths, through coral, through mind, winding. My god, my god, why hast though forsaken me? Meaning does not inhere. Memory wastes. Materiality fades in the face of the monstrance. Moon, moraine, monosyncline, monsoon. Make of this what you can, for it is certain that you will (l)anguish without protection once god has died. Moreover, he dies again each time he is denied. Mons veneris, unclimbable. Mourning. Miracle is not to have been born at all.

Mystery

Nuncios

reflect upon diplomatic slights, remembered for centuries. Nuncupate wills bequeath only resentment. No-one knows how to end the blood feud between god and the gods. Nor even God himself … not love that I’m running from, just the heartache I know will come. Nepenthes priced beyond your range, nates of loss, neuralgia of the wizened hand. Never again, never before, never more, never never. Nymph in thy orisons … Now anticipates next, next recalls last.

Nectar

Opium

of the masses, law of the discarded middle, oxygen of love, orisons, torsions … O.K. means orl korrect (joc.). On the far side of the ocean, a chemical sea, washing the ferrous sand with its salts. Oleaginous life, clinging to the margins. O western wind, when wilt thou blow? Omphalos. Omit no time. Oligocene to now, epoch of the primates. Opus terminus of the god of all this … order. Or chaos, whichever you prefer. Orb and oblate of the orient. Enceinte.

Old

Primate

of all England, a monkey in robes, wearing a mitre. Primordial delusion, priapic vanity, primum mobile. Perhaps it is time to leave the gods to their own devices, perhaps god’s away on business. Pulsars at the furthest edge of the universe engage his attention. Persuasion will do no good, prayer is useless, promises will not be kept. Puer aeternis in a gavotte with a senescent priest. Pinions engage the clockwork of creation. Plangent, placid, all but played out.

Pluto

Quean

of the imaginary, quatorzain of love, quaternary delusion. Quite why we are here nobody really knows. Quantity or quality remains an incommensurable choice. Quavery voice of the aeons proclaims the eternal recurrence of all things. Questions without answers, answers without questions. Quandary: quarks quark, queers queer, quid or quiddity, who knows? Qur’an is god’s last book? Quiet of evening, stillness of water, faint braille of stars on black quilt of sky.

Quill

Recent

retreats of ice recall earlier epochs, a watery world. Radio love broadcasts on all frequencies, without ratiocination. Railways run to the end of the earth, a train leaves the last platform and climbs into the sky. Round the rugged rocks the ragged rascals … three, three the rivals. Rapturing in a ratskeller. Raucous birds calling from the future, the one god will not see. Reptiles wore feathers in the Jurassic, a rubefaction of time. Rehearsal for undermining, catastrophic reprise.

Rain

Snake

in the garden, saying: Ye shall not surely die. Seismic shift, shatter of bones, eyes opening on the unseen. Saying: Seek and ye shall find. Serein, falling from a cloudless sky, at evening. Saraband or serenade, swansdown of sublunary light, skin sere like old leather. Shofar sounds on the baked plains of Jericho, walls do not fall. Sheer drop, shot silk, satin and lace. Seductive world, how not to eat of god’s apple? Sea pink, sea kale, sea angel, sea horse. Silver and gold.

Song

Triage

of gods, who shall we examine first? Take which fiction to task? Tragacanth for the holy spirit will come, by tumbrel, from the west. Twice told tales of fathers and sons. Tryst or triste? Tomb of reality, trapeze without net, machine without a ghost: this Universe. Tuberous spring, tubercular summer, tumult of autumn, winter of total war. Tessera to enter the Coliseum, where tranced men and beasts contend. Tertian fever. Trumpery of a tired theology.

Time

Umbelliferous

dark. Understanding nothing but, yes, standing under the stars. Unreal City, the capital of Ultima Thule. Unmarked trams spark through the murk, rendezvousing with the Underground at Central. Until you have been unsexed you will not know god’s uttermost ecstasy. Utopia the last stop on the suburban line. Uvular speech. Usurious, uxorious, useless man. Undine spoke last of all, what she said made no sense to anyone not already a water nymph.

Urn

Venusian

inspection of Earth discloses conditions inimical to life as they know it. Verglas clogs in their lungs. Viruses insinuate themselves into their DNA, visiting the future by proxy. Vaster than empires and more slow. Voluptuous time, veridical miracle. Vomer broken by a blow to the face. Vulgarity of blood on god’s lips. Vatic speech interrupted in the forum by an irruption of Goths, Huns, Vandals. Vulcanized rubber on wheels of carts trundling towards eternity.

Vulva

Windows

glazed with yellow light on god’s last afternoon in the world. Worth every minute, it was. Wandered into the Wendy house, looking for laughter. Wasn’t there. When, when and whenever death closes our eyelids … We cannot say why, nor can we stop asking. Wolfram mined in dark valleys, welded to make the adamantine gates, out in the autonomous zone. Whirled beyond the stars, wreathed in sorrow, wrecked. Wraiths at his wittering lips, awaiting the end.

Wind

Xanthe

heartless, unfaithful, beautiful, where did you go? Xoanon of some mysterious god, fallen from heaven, worshipped by barbarians, why? X marks the spot where I wept for you, the yellow acids of the earth staining my skin. Xenophobes gather under the portico, announcing my exile. X rays of my heart show a blackened core, drier than dust. Xeroxs of you proliferate everywhere I go, copies of copies of copies, each generation a little more blurred than the last.

Xylem

Yare

yare, good Iras; quick. Ytterbium or yttrium? You cannot say where in the lanthanides this silvery or greyish metal occurs. Years later, we come again to the yarborough where no number over nine is admitted. Yardbirds rehearse their back and forth, endlessly. Youth is wasted on the young; yet how could it be otherwise? Yawing of a yacht from its course; yaws, passed venereally, colouring the skin red. Yes, anticipate the godly light. Y chromosome, yearning for an X.

Yield

Zac

tanner, a sixpence for her shoe ... Zener cards prove that intuition exists, zig-zagging through consciousness like an unused road. Zenith of possibility, zen of nullity, immured in the zenana. Zodiacal light in the east, tall triangle, after sunset. Zircon nights we danced heedlessly away, in another time, before we lost each other unaccountably and forever. Zygote of the single flight, zeroth of love, gamin inexistent and desired as god, unzip my chest and so remove my heart.

Zero

1.12.06

Elurea

Sometimes in dreams you meet people who seem to all intents and purposes, real. And I'm not talking about succubi, not this time. It was up in Paddington, I was working a shift, but had for some reason taken a break. At the bar of a hotel in Oxford Street, ordering a (soft) drink. She came up beside me, smiled and suggested I ask her out sometime. To a movie or a dance. So I did.

She was slender and small, though not tiny. Later that same evening we were walking together in another part of Oxford Street, holding hands. Her hands were different from each other, the left was littler and a bit wizened, the right fuller and smoother. A close friend of mine was with us, I knew she was looking at us holding hands and wondering what it meant.

Later still, back at the cab, which was in fact my own car, parked under dark trees near the Paddington Town Hall, I said, yes, I'll take you back to Elurea. This meant somehow fitting her pushbike into the boot of the car, but we managed it. And off we went. The final image of the dream was a map reference, Elurea, far to the south of the City, north facing, on the shores of the Georges or the Hacking River. I woke with a strong sense of the sweetness of person of this nameless woman. Wanting to see her again. Absurd as that sounds.

So I went to my Sydway for a look in the south ... the suburb that corresponds to the map in the dream is Illawong, somewhere I've never been, a place I was only vaguely aware of, on the south bank of the Georges River. Yesterday, it's true, I was looking at Sydney's outer suburbs, but I was looking in the north: at Glossodia, Ebenezer, Sackville, Maroota and Fiddlertown.

Then, I googled the dream name, trying various spellings: both Illuria and Eluria are places with established, if fictive, existences, so I settled on the spelling above, even though, in the dream, I thought it was probably Illuria we were going to.

How now will I find my way back to Elurea? And, when I do, will she be waiting there for me? By the wharves, perhaps, at the end of Letter Box Lane?

She was slender and small, though not tiny. Later that same evening we were walking together in another part of Oxford Street, holding hands. Her hands were different from each other, the left was littler and a bit wizened, the right fuller and smoother. A close friend of mine was with us, I knew she was looking at us holding hands and wondering what it meant.

Later still, back at the cab, which was in fact my own car, parked under dark trees near the Paddington Town Hall, I said, yes, I'll take you back to Elurea. This meant somehow fitting her pushbike into the boot of the car, but we managed it. And off we went. The final image of the dream was a map reference, Elurea, far to the south of the City, north facing, on the shores of the Georges or the Hacking River. I woke with a strong sense of the sweetness of person of this nameless woman. Wanting to see her again. Absurd as that sounds.

So I went to my Sydway for a look in the south ... the suburb that corresponds to the map in the dream is Illawong, somewhere I've never been, a place I was only vaguely aware of, on the south bank of the Georges River. Yesterday, it's true, I was looking at Sydney's outer suburbs, but I was looking in the north: at Glossodia, Ebenezer, Sackville, Maroota and Fiddlertown.

Then, I googled the dream name, trying various spellings: both Illuria and Eluria are places with established, if fictive, existences, so I settled on the spelling above, even though, in the dream, I thought it was probably Illuria we were going to.

How now will I find my way back to Elurea? And, when I do, will she be waiting there for me? By the wharves, perhaps, at the end of Letter Box Lane?

30.11.06

gone to god

After yesterday's post (was it?) I almost remembered what this site was meant to be about. At the beginning. Almost but not quite. And, I don't really want to. As if some things were better left dead. Admonitions that we need entertain no longer. Again ... this sense of instability, a wandering wondering what is the real state of mind? Among the myriad that we pass through, or that pass through us, in a minute, an hour, a day, which one is the real? A real? All.

29.11.06

dreaming's end / ending's dream

Sometimes life just seems to stop. Or, it is elsewhere. In the Andromeda galaxy perhaps. The absence of god, in whom you do not believe, seems more profound than ever. Divinity further away than the furtherest quasar. These periods of non-life come without warning and last for eternity or for a day, whichever is longer. Several days, a week, a fortnight go by and nothing happens. It isn't that the sun does not rise, the moon wax or wane, traffic circulate like blood platelets in the City's hardening arteries. It's not that eating and sleeping, working and not working, walking, reading, talking, remembering and forgetting cease to engage or distract you. But, through and by and because of and besides all that, life has stopped. Then one day it starts again, and it is only now you can say: Life had stopped.

13.11.06

Nothing has changed here. The privilege of stones?

They always are, for that is the way they like it.

Czesław Miłosz: from The Rising of the Sun, VII, Bells in Winter

Si j'ai du goût, ce n'est guères

Que pour la terre et les pierres.

This "taste for stone" is a theme in modern literature that emerges in the early days of Romantic writing and flows like a submerged river through practically all serious works in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It stems from the classical feeling that stone was a dead substance and therefore belonged to a separate realm of being. Hades, for instance, was stone, as was the dead moon. The firm Greek sense that stone does not grow distinguished it radically from things that do. And yet it was of mineral substance that everything was made: an organism was an interpenetration of matter and spirit.

Put the understanding another way: science and poetry from the Renaissance forward have been trying to discover what is alive and what isn't. In science the discovery spanned three centuries, from Gassendi to Niels Bohr, and the answer is that everything is alive.

Poetry has a similar search, and its answer is not yet formulated, as it cannot understand nature except as a mirror of the spirit ...

Guy Davenport: from Olson, in The Geography of the Imagination, Forty Essays

They always are, for that is the way they like it.

Czesław Miłosz: from The Rising of the Sun, VII, Bells in Winter

Si j'ai du goût, ce n'est guères

Que pour la terre et les pierres.

This "taste for stone" is a theme in modern literature that emerges in the early days of Romantic writing and flows like a submerged river through practically all serious works in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It stems from the classical feeling that stone was a dead substance and therefore belonged to a separate realm of being. Hades, for instance, was stone, as was the dead moon. The firm Greek sense that stone does not grow distinguished it radically from things that do. And yet it was of mineral substance that everything was made: an organism was an interpenetration of matter and spirit.

Put the understanding another way: science and poetry from the Renaissance forward have been trying to discover what is alive and what isn't. In science the discovery spanned three centuries, from Gassendi to Niels Bohr, and the answer is that everything is alive.

Poetry has a similar search, and its answer is not yet formulated, as it cannot understand nature except as a mirror of the spirit ...

Guy Davenport: from Olson, in The Geography of the Imagination, Forty Essays

10.11.06

more about stones

When I first came to Sydney in 1981, I lived in Thomas Street, Chippendale, as it was then called, though properly it was Darlington and sometimes known as Redfern. Near one of the lost suburbs, Golden Grove, which now survives only as a street name. Anyway. A friend mentioned to me one day how you would sometimes find unusual stones around there, stones that looked as if they had been brought from elsewhere and placed, for some inscrutable reason, on a corner, next to a doorway, on a curb ... not long after he pointed this out to me, I found one of these stones in nearby Vine Street, not far from a big old sandstock curb that had the baleful letters K I L L inscribed in it, as if by some disaffected quarrying convict. I picked up this stone and kept it near me for many years, losing sight of it, unaccountably, when I left Pearl Beach to move back into the City a couple of years ago. It's probably still up there somewhere.

It was small enough to fit comfortably in the palm of my hand, irregularly shaped, very hard, and pitted all over. The upper surface was dark and rounded but, underneath, it was slightly concave and of a much paler colour, as if it had sat for a long time half in, half out of water. Someone I showed it to once told me that there are stones like that lying around about the blowhole at Kiama, on the South Coast. Maybe that's where it came from. Who brought it? Thomas Street is very close to The Block, where an urban Aboriginal community hangs on despite the many efforts from local and State government instrumentalities to re-locate them elsewhere. I used to wonder if these mysterious stones were an occult intervention in the psychogeography of the City but perhaps that's too romantic a notion.

And yet ... the other day, Friday, after I picked my sons up from Strathfield station, we were wandering back down Parnell Street to the car when I spotted another unusual stone, lying in the grass outside some double doors to somebody's garage or back yard. This, like the Kiama stone, is very hard and pitted all over, but it's quite a bit larger and the surface below the pits is a rust orange colour. It's much more regular in shape, indeed, it looks as if it has been worked to make a flattened ovoid, though exactly how you'd work a stone this hard is beyond me. It's just the way there's a slight ridge around the circumference when you lie it flat. This stone also fits comfortably in my hand, but only with my fingers and thumb curled around it. Feels good to heft. Would make an excellent grindstone and, if it is any kind of artefact, that's probably what it's for.

The impulse to pick up and carry away these stones is very strong but it's not unquestionable. If they are placed, shouldn't they be left there? Or, is it the case that they are placed in order that they be found and used again? I'm unlikely to grind with this stone but I will keep it and value it as long as it stays with me - and perhaps that's all a stone asks. Czeslaw Milosz says somewhere that stone is stone because it only wants to be stone. And yet ... who has not heard, at some estranged or estranging moment, the stones cry out to us?

It was small enough to fit comfortably in the palm of my hand, irregularly shaped, very hard, and pitted all over. The upper surface was dark and rounded but, underneath, it was slightly concave and of a much paler colour, as if it had sat for a long time half in, half out of water. Someone I showed it to once told me that there are stones like that lying around about the blowhole at Kiama, on the South Coast. Maybe that's where it came from. Who brought it? Thomas Street is very close to The Block, where an urban Aboriginal community hangs on despite the many efforts from local and State government instrumentalities to re-locate them elsewhere. I used to wonder if these mysterious stones were an occult intervention in the psychogeography of the City but perhaps that's too romantic a notion.

And yet ... the other day, Friday, after I picked my sons up from Strathfield station, we were wandering back down Parnell Street to the car when I spotted another unusual stone, lying in the grass outside some double doors to somebody's garage or back yard. This, like the Kiama stone, is very hard and pitted all over, but it's quite a bit larger and the surface below the pits is a rust orange colour. It's much more regular in shape, indeed, it looks as if it has been worked to make a flattened ovoid, though exactly how you'd work a stone this hard is beyond me. It's just the way there's a slight ridge around the circumference when you lie it flat. This stone also fits comfortably in my hand, but only with my fingers and thumb curled around it. Feels good to heft. Would make an excellent grindstone and, if it is any kind of artefact, that's probably what it's for.

The impulse to pick up and carry away these stones is very strong but it's not unquestionable. If they are placed, shouldn't they be left there? Or, is it the case that they are placed in order that they be found and used again? I'm unlikely to grind with this stone but I will keep it and value it as long as it stays with me - and perhaps that's all a stone asks. Czeslaw Milosz says somewhere that stone is stone because it only wants to be stone. And yet ... who has not heard, at some estranged or estranging moment, the stones cry out to us?

5.11.06

The Dogon Stones

Last year I filled out a coupon from a newspaper and subsequently received a free copy of the 11th edition of The Times Comprehensive Atlas of the World ... in the same act committing myself to buying four other books from the relevant source. Knew this was a mistake but wanted the Atlas ... love the Atlas. Took months of distraction to decide which among those available I would choose for my four purchases; meanwhile the junk mail quotient in my letter box increased exponentially. Because the original source misspelled my name, I can always tell when they've handed it on to someone else. All sorts of dubious people. Anyway, settled finally on a book for each for my sons - The Siege and Fall of Troy, Robert Graves' re-telling of The Iliad; The Wind in the Willows; - plus Brewer's Dictionary of Rogues, Villains, & Eccentrics (a disappointment); and The Life of Muhammad.

Have just started to read this last, by Ibn Ishaq, who was born in Medina about 85 years after the hijra of AD622 and died in Baghdad 66 years later. His inaugural biography survives only in a version edited by Ibn Hisham, who himself died about 60 years after Ibn Ishaq. The translation is by Hungarian Edward Rehatsek, made in Bombay and completed just before his own death in 1891. This voluminous work was, in its turn, edited by Michael Edwardes to make a slender, elegantly produced and written book of about 150 pages, first published in 1964. Somewhat to my surprise, I am enjoying it immensely. I love its mix of family and tribal history, folktale, hokum and divine revelation. Among the much I did not know about the subject is that the pre-Muslim Arabs of Mecca and Medina worshipped gods who were enshrined in stones. Nor did I know that the Kaba, which includes in itself a Black Stone that is thought to be a meteorite, predates Islam. You could perhaps say that the worship of stones has survived the advent of the Koran.

These disparate facts made me think of an encounter I was lucky enough to have, years ago now, with two remarkable stones from Africa. I knew, through my girlfriend at the time, a fellow called Ken de la Coeur. Ken was a Qantas steward who spent his time off in West Africa, buying all sorts of things that he would then bring back to Australia for resale. Anything from vast wooden canopied beds to tiny coloured beads made out of Venetian glass that had been melted down and then recast. Many of his things were rare and, since he had a good eye, all of them were beautiful. My girlfriend met him because she used to go into the shop he had on King Street, Newtown to trawl through that vast array. Ken didn't actually sell much, that wasn't really the point. Instead, he amassed a unique collection of West African art, mostly sourced from select dealers whom he'd got to know, and visited on his regular trips.

Ken loved the people of West Africa as much as their art, and it was probably from one of the men he met there that he contracted HIV. In time, he became too ill to keep the shop open, but he continued to run the business, such as it was, from his home in Redfern. After his last trip to West Africa, he held a soirée to which guests, mostly personal friends, were invited to come and view, perhaps purchase, his latest acquisitions. We were among the first to arrive at that event, and the last to leave. Very late in the evening, when there were just a few people still there, he brought out and unwrapped two stones that came, he said, from among the Dogon people of Mali. It is difficult for me describe the aura possessed by these two stones, one of which was male, one female. They were about the size of a small cantaloupe, ovid, reddish, one larger and darker than the other. I held them for a long time and did not want ever to let them go. Ken was asking a thousand dollars for the pair, far too much for me to consider buying them. In the end I did give them back and he re-wrapped them in their cloth and put them away.

Ken was from Melbourne. His family, whom I met at the wake, although they loved him, had never accepted that he was gay; and yet, when it came to his will, it turned out he left everything to them. Perhaps a worse tragedy was, he'd never catalogued his collection. His knowledge was extraordinary but most of what he knew wasn't written down. It was all in his head. You only had to point to something for Ken to tell you in detail its origin, provenance, significance and all sorts of other information about it. This knowledge went with him to his grave. As for the collection, the family gathered it up and shipped it to a warehouse in Melbourne. Later, I understand, it was broken up and sold. Most of it would have been represented only by the tiny cardboard tags, with Ken's fine calligraphy on them, that he would attach to his things. They would include a brief description, the location it came from, and a price - no more.

The stones, when I saw them, were not accompanied by any written description at all. They were probably, despite their size, of the kind worn in massive iron necklaces by Hogon or wise men; if so, they represented bones and were a source of power. I often wonder what happened to them, whether they were sold, or if they were thrown out or abandoned - after all, what use to anyone is an anonymous rock? Or perhaps not, perhaps the power that emanated from them meant that they have been acquired by someone who knows something of what they are. It is impossible to tell. I only had two things of Ken's: a small example of one of the afore-mentioned Venetian glass beads that he gave me, handed on recently to a dear friend for her fiftieth birthday. The other is a small bronze box, with three pairs of birds on the lid, facing each other, their beaks fused, that my girlfriend gave me. I do not know where the little card that came with it is now, though I may still have it. And yet there is a third: an indelible memory of the Dogon Stones.

Have just started to read this last, by Ibn Ishaq, who was born in Medina about 85 years after the hijra of AD622 and died in Baghdad 66 years later. His inaugural biography survives only in a version edited by Ibn Hisham, who himself died about 60 years after Ibn Ishaq. The translation is by Hungarian Edward Rehatsek, made in Bombay and completed just before his own death in 1891. This voluminous work was, in its turn, edited by Michael Edwardes to make a slender, elegantly produced and written book of about 150 pages, first published in 1964. Somewhat to my surprise, I am enjoying it immensely. I love its mix of family and tribal history, folktale, hokum and divine revelation. Among the much I did not know about the subject is that the pre-Muslim Arabs of Mecca and Medina worshipped gods who were enshrined in stones. Nor did I know that the Kaba, which includes in itself a Black Stone that is thought to be a meteorite, predates Islam. You could perhaps say that the worship of stones has survived the advent of the Koran.

These disparate facts made me think of an encounter I was lucky enough to have, years ago now, with two remarkable stones from Africa. I knew, through my girlfriend at the time, a fellow called Ken de la Coeur. Ken was a Qantas steward who spent his time off in West Africa, buying all sorts of things that he would then bring back to Australia for resale. Anything from vast wooden canopied beds to tiny coloured beads made out of Venetian glass that had been melted down and then recast. Many of his things were rare and, since he had a good eye, all of them were beautiful. My girlfriend met him because she used to go into the shop he had on King Street, Newtown to trawl through that vast array. Ken didn't actually sell much, that wasn't really the point. Instead, he amassed a unique collection of West African art, mostly sourced from select dealers whom he'd got to know, and visited on his regular trips.

Ken loved the people of West Africa as much as their art, and it was probably from one of the men he met there that he contracted HIV. In time, he became too ill to keep the shop open, but he continued to run the business, such as it was, from his home in Redfern. After his last trip to West Africa, he held a soirée to which guests, mostly personal friends, were invited to come and view, perhaps purchase, his latest acquisitions. We were among the first to arrive at that event, and the last to leave. Very late in the evening, when there were just a few people still there, he brought out and unwrapped two stones that came, he said, from among the Dogon people of Mali. It is difficult for me describe the aura possessed by these two stones, one of which was male, one female. They were about the size of a small cantaloupe, ovid, reddish, one larger and darker than the other. I held them for a long time and did not want ever to let them go. Ken was asking a thousand dollars for the pair, far too much for me to consider buying them. In the end I did give them back and he re-wrapped them in their cloth and put them away.

Ken was from Melbourne. His family, whom I met at the wake, although they loved him, had never accepted that he was gay; and yet, when it came to his will, it turned out he left everything to them. Perhaps a worse tragedy was, he'd never catalogued his collection. His knowledge was extraordinary but most of what he knew wasn't written down. It was all in his head. You only had to point to something for Ken to tell you in detail its origin, provenance, significance and all sorts of other information about it. This knowledge went with him to his grave. As for the collection, the family gathered it up and shipped it to a warehouse in Melbourne. Later, I understand, it was broken up and sold. Most of it would have been represented only by the tiny cardboard tags, with Ken's fine calligraphy on them, that he would attach to his things. They would include a brief description, the location it came from, and a price - no more.

The stones, when I saw them, were not accompanied by any written description at all. They were probably, despite their size, of the kind worn in massive iron necklaces by Hogon or wise men; if so, they represented bones and were a source of power. I often wonder what happened to them, whether they were sold, or if they were thrown out or abandoned - after all, what use to anyone is an anonymous rock? Or perhaps not, perhaps the power that emanated from them meant that they have been acquired by someone who knows something of what they are. It is impossible to tell. I only had two things of Ken's: a small example of one of the afore-mentioned Venetian glass beads that he gave me, handed on recently to a dear friend for her fiftieth birthday. The other is a small bronze box, with three pairs of birds on the lid, facing each other, their beaks fused, that my girlfriend gave me. I do not know where the little card that came with it is now, though I may still have it. And yet there is a third: an indelible memory of the Dogon Stones.

4.11.06

Diptych

One

Bruno’s Indian said something wise as I was leaving but, like so much of the wisdom that has come my way, I have forgotten it. He was a tall, slender young man, the foreman of the gang of Gujarati illegals who picked Bruno’s apples and pumpkins, but even his natural authority could not make them work on festival days, nor on the days when, for reasons that were obscure, they became spooked. I saw him in the rearview mirror, dressed in white, standing with my sister and her husband as I drove away from the sheds on the rich river flats down by the Tuki Tuki and then on out of the valley.

The back seat of the rental car was full of crisp red apples and my sister had given me some of the strong dope they grew in a favoured spot in the orchard. I was going to Wellington for an art opening, via south Hawkes Bay and the Wairarapa, intending to stop in a town of my youth to visit my father’s grave. I was happy to be free and untrammelled on the road, but throughout the morning and the early afternoon, a troubling image kept surfacing and floating before my mind’s eye: the bones of my father’s skull coming through the flesh down there in the earth where we'd buried him a couple of years before.

After I left Masterton I smoked a joint rolled previously which, while it did not banish the visage of the skull beneath the skin, did overlay it with intensely nostalgic images from my boyhood; so that when I crossed the bridge over the Waiohine, just north of Greytown, and saw kids swimming as I used to do in the swift green waters between the piles, I turned off the road and drove down the short track to the stony river beach where they had left their piles of clothes and their towels draped over gorse or broom bushes. But it was no longer possible for me to join them, so soon enough I reversed and turned about and bumped back up to the highway and on.

The graveyard is south of the town, with curiously shaped concrete wings over the gate that do not meet to make the arch they suggest. I had never explored it properly before, and was surprised to find it segregated: a small Jewish section and then the Catholics there on the right as you went up the drive, with a row of truncated macrocarpas on the left, behind which my father lay. Over the cattlestop and into the main part of the cemetery. I stopped the car near a small wooden shed built next to the boundary fence, climbed out, stretched. I was feeling strange already, otherwordly, perhaps trepidated, if that’s a word.

It was a still, partly cloudy afternoon, alternately bright and shadowed, and quiet except for the carolling of magpies from the tall pine trees up the back and the seemingly grief-stricken, intermittent cries of sheep from the surrounding paddocks. I walked over to the Sexton’s shed and peered through the dusty, spider-webbed window. Its floor was uneven, a turmoil of earth, as if someone had tried to excavate within. A broken shovel lay sideways in the dirt and there did not appear to be any back wall to it. That chaos of scumbled filth went forever. It was like a vision, not so much of hell, but of some brute vacuum beyond both heaven and hell. I felt myself being pulled into that vortex and it was an effort to drag myself away. The illusion so strong I went around the back to check if there was in fact a wall there …

A low hedge grew over the fence on that side of the graveyard and from in amongst its tangled greenery, its twiggy darkness, I could hear the rustling of some small animal or bird. There was another shed further along, I walked towards it as if impelled by the foreboding atmos around me. It was more miniature barn than shed, with double wooden doors, one of which was half open, the other secured with a bolt. The open side held more tools, a mower, fuel cans and so forth. I shot the bolt on the other door, it creaked open. Inside was a pile of yellow straw and laid on the straw, unaccountably, was the mummified body of a whippet or a small greyhound. The roar building in my ears became louder, I swayed, dizzy, faint. The body of the dog filled me with horror, the rustling in the hedgerow likewise. I closed the door and stumbled away.

Up the back of the graveyard, under the huge, raggedy pines, is a rectangular field in which are a couple of dozen massive, elaborate, nineteenth century graves all set on a diagonal with respect to the parameters of the enclosure. As I walked into that field, the sun went behind a cloud, the magpies flew up, with loud cries, out of the pines and away. The roaring in my ears crescendoed and I seemed to hear, above or below or amongst it, the grumbling voices of the dead town fathers and mothers buried here, a stern and heartless rehearsal of the Anglican pieties that ruled the town. The graves were disposed, I thought, on a ley line that stretched, past the brown hills to the northeast, over the manifold ocean, all the way back to some dim, occulted village in England.

No! I said, or shouted, though not out loud. No, no, no! I would not submit to their dread authority, I was not subject to their haunting, they could not own my soul the way they thought they owned the soul of the town. Their dead hand could fall where it would, but not on my sleeve, nor my shoulder, not on your life. I walked among the old graves, reading the names, muttering my refusals, and heard the ancient voices diminish to a murmur of discontent then die away into the dark and bright light of the afternoon.

Whatever it was, or had been, was over. I left that baleful field and made my way back through the military section to where my father lay. When we buried him I brought two stones for his grave, one from each of the two rivers that run through the town where I was born. The round one, like a skull, that I found at the bend in the Mangawhero where we used to go swimming, was set in concrete at the head of the grave, but the wide flat footstone I pulled out of the Mangateitei on the slopes of the mountain was missing. I stood where it should have been and spoke a few words out loud to him; then was quiet. The decay of his body no longer worried me. I even felt a kind of peace descend, neither profound nor momentous, but ordinary, mortal. In that silence, that peace, I heard the ticking of his watch on my wrist.

Two

The morning after the opening, I hit the road again, driving back to Auckland via Taranaki. I had someone to see, a rich art collector, in New Plymouth. I stayed the night in a motel at Waitara, then continued on up Highway 3, which runs along that wild coast as far as Mokau. I smoked another joint of my sister’s strong dope as I left town which, again, might explain the experience I was about to have. On the other hand, things like this have happened to me, unpredictably, when I’ve been unstoned, or stone cold sober.

I was barrelling down a wide empty sweep of highway towards a river bridge when I felt a sudden urge to stop. I drove over the bridge and turned off to the right, onto an obscure country dirt road. No, this wasn’t it. I turned the car around, went back, re-crossed the bridge and took another road that ran along the side of the river towards the sea. There was a carpark and picnic area about a kilometre along. I left the car there, intending to walk out along the tidal riverbed to the sea.

It was mid morning. A fine day. The tide was out. I took off my shoes, left them where I could easily find them again and set off across mudflats towards a high ridge of black iron sand, glinting with mica. It squeaked as my feet sank into it, leaving behind sighing holes that soon filled up with sand trickles. Past this ridge I could see a curiously truncated headland made of yellowish-brown sandstone, capped with tough grass. Fragmentary islands of the same rock out in the sea. I thought if I could get around this promontory I might find an ocean beach beyond.

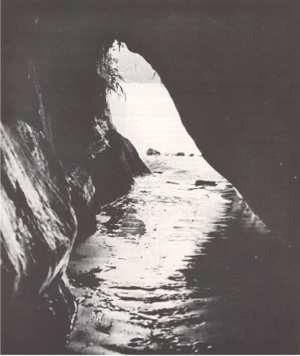

The walk was longer than I expected, and as I neared the head of the headland I saw that it was riven through by a cave that might or might not go all the way to the other side. The dark aperture of the cave mouth seemed forbidding or forbidden so I plodded on, round the point and out onto a wide beach that stretched away south for kilometres. There before me, at the back of the high tide line, stood a strange, weather-beaten structure, shiny and white as bones. It resembled one of those stages that were made to lay out the bodies of the dead until all the flesh had gone from the bones, which would then be cleaned and gathered together and hidden away in some cave.

It even looked, from a distance, as if there might be bones upon it, but as I moved closer I saw it was not so: just a platform made out of driftwood, about a metre tall and two metres broad. Lashed together with baling twine that was already pale and fraying. What on earth was it for? Who had made it? Why? It was as foreboding as it was mysterious. I sat down next to it and wondered; then, since the day was warm and there was no-one around, took off all my clothes and went down into the surf.

A perfect set, seven waves, rolled in as I walked out, and I caught the last of them and shot shoreward in a hiss and bubble and surge of white water. Beautiful. Out again I went, and in on another perfect wave. And again, and again. I was as if drunk with exaltation and it wasn’t until, shivering with cold, I finally, regretfully, left the water and went back up to where my clothes were that I realised the tide was coming in—fast. The sea was already lapping at the base of the stubby yellow-brown headland where, moments ago, as it seemed, I’d walked across crunchy dry black sand.

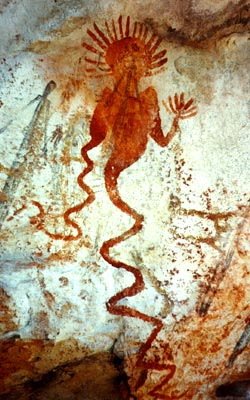

In a panic now, I threw on my clothes and started back. It was too late to return as I had come, the only way was via the cave which did in fact go right through the headland. The premonitory fear I’d felt before was still with me but the urge to reach the other side before the tidal river became impassable was stronger. Sea water was sliding into the cave mouth as I entered, starting to run. So it was that the markings on the cave walls, the ancestral figures with triangular heads and slanted eyes, the chevrons and the double spirals, and, upright along the walls, the many stylised feet, three and four and six and seven-toed, the toes made of holes drilled in the rock, passed in the blur. And yet I seemed to hear a hiss of voices as I ran, a jostling, archaic, sibilant chorus which might just have been the waves of the sea, advancing.

It was hard to move at speed across that long black reach of glittering sand, and exhausting too, and by the time I was over it, the tidal river was knee deep; when I’d waded back to where my shoes were, under a flax bush on a clod of earthy bank, my trousers were wet to the thighs and my heart was going like billy-o. But that was alright; I was safe.

It wasn’t until I got to Auckland and looked at the catalogue of the art opening I’d attended in Wellington, that I realised where I’d been: Tongaporutu, Tony Fomison writes in a 1980 essay reprinted towards the back of What shall we tell them?, is the largest rock art site in Taranaki. Here wayfarers, or war parties, paused on the main Waikato to Taranaki track. Here, perhaps, the ceremony called uruuruwhenua was performed. Fomison quotes James Cowan: If you wish to avoid heavy rain or other obstruction or inconvenience on your day’s journey, you must pay due respect to Tokahaere (a ‘walking rock’ in the King Country) by pulling a handful of fern or manuka and laying it at his foot, reciting as you do an ancient prayer to the spirit of the rock …

I did not of course have the time for such a ceremony, even if I'd known what it was. All I had was a glimpse of an antique mystery, a once sacred place that is now a curiosity and will soon disappear under the inexorable rise of the ocean, as so many other sites that existed along that coast already have done. Yet I drove away over the bridge and up the wide sweet highway on the other side with a clean feeling, as if the sea, though not perhaps the cave, had scoured my skin of the accretion of those half-formed, half-unadmitted residues of the flotsam we pick up as we live through our days. As if I had been, momentarily, serendipitously, reborn.

Bruno’s Indian said something wise as I was leaving but, like so much of the wisdom that has come my way, I have forgotten it. He was a tall, slender young man, the foreman of the gang of Gujarati illegals who picked Bruno’s apples and pumpkins, but even his natural authority could not make them work on festival days, nor on the days when, for reasons that were obscure, they became spooked. I saw him in the rearview mirror, dressed in white, standing with my sister and her husband as I drove away from the sheds on the rich river flats down by the Tuki Tuki and then on out of the valley.

The back seat of the rental car was full of crisp red apples and my sister had given me some of the strong dope they grew in a favoured spot in the orchard. I was going to Wellington for an art opening, via south Hawkes Bay and the Wairarapa, intending to stop in a town of my youth to visit my father’s grave. I was happy to be free and untrammelled on the road, but throughout the morning and the early afternoon, a troubling image kept surfacing and floating before my mind’s eye: the bones of my father’s skull coming through the flesh down there in the earth where we'd buried him a couple of years before.

After I left Masterton I smoked a joint rolled previously which, while it did not banish the visage of the skull beneath the skin, did overlay it with intensely nostalgic images from my boyhood; so that when I crossed the bridge over the Waiohine, just north of Greytown, and saw kids swimming as I used to do in the swift green waters between the piles, I turned off the road and drove down the short track to the stony river beach where they had left their piles of clothes and their towels draped over gorse or broom bushes. But it was no longer possible for me to join them, so soon enough I reversed and turned about and bumped back up to the highway and on.

The graveyard is south of the town, with curiously shaped concrete wings over the gate that do not meet to make the arch they suggest. I had never explored it properly before, and was surprised to find it segregated: a small Jewish section and then the Catholics there on the right as you went up the drive, with a row of truncated macrocarpas on the left, behind which my father lay. Over the cattlestop and into the main part of the cemetery. I stopped the car near a small wooden shed built next to the boundary fence, climbed out, stretched. I was feeling strange already, otherwordly, perhaps trepidated, if that’s a word.

It was a still, partly cloudy afternoon, alternately bright and shadowed, and quiet except for the carolling of magpies from the tall pine trees up the back and the seemingly grief-stricken, intermittent cries of sheep from the surrounding paddocks. I walked over to the Sexton’s shed and peered through the dusty, spider-webbed window. Its floor was uneven, a turmoil of earth, as if someone had tried to excavate within. A broken shovel lay sideways in the dirt and there did not appear to be any back wall to it. That chaos of scumbled filth went forever. It was like a vision, not so much of hell, but of some brute vacuum beyond both heaven and hell. I felt myself being pulled into that vortex and it was an effort to drag myself away. The illusion so strong I went around the back to check if there was in fact a wall there …