empty of future, renew the sign: lucent paradox, ineluctable trace ...

30.11.06

gone to god

After yesterday's post (was it?) I almost remembered what this site was meant to be about. At the beginning. Almost but not quite. And, I don't really want to. As if some things were better left dead. Admonitions that we need entertain no longer. Again ... this sense of instability, a wandering wondering what is the real state of mind? Among the myriad that we pass through, or that pass through us, in a minute, an hour, a day, which one is the real? A real? All.

29.11.06

dreaming's end / ending's dream

Sometimes life just seems to stop. Or, it is elsewhere. In the Andromeda galaxy perhaps. The absence of god, in whom you do not believe, seems more profound than ever. Divinity further away than the furtherest quasar. These periods of non-life come without warning and last for eternity or for a day, whichever is longer. Several days, a week, a fortnight go by and nothing happens. It isn't that the sun does not rise, the moon wax or wane, traffic circulate like blood platelets in the City's hardening arteries. It's not that eating and sleeping, working and not working, walking, reading, talking, remembering and forgetting cease to engage or distract you. But, through and by and because of and besides all that, life has stopped. Then one day it starts again, and it is only now you can say: Life had stopped.

13.11.06

Nothing has changed here. The privilege of stones?

They always are, for that is the way they like it.

Czesław Miłosz: from The Rising of the Sun, VII, Bells in Winter

Si j'ai du goût, ce n'est guères

Que pour la terre et les pierres.

This "taste for stone" is a theme in modern literature that emerges in the early days of Romantic writing and flows like a submerged river through practically all serious works in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It stems from the classical feeling that stone was a dead substance and therefore belonged to a separate realm of being. Hades, for instance, was stone, as was the dead moon. The firm Greek sense that stone does not grow distinguished it radically from things that do. And yet it was of mineral substance that everything was made: an organism was an interpenetration of matter and spirit.

Put the understanding another way: science and poetry from the Renaissance forward have been trying to discover what is alive and what isn't. In science the discovery spanned three centuries, from Gassendi to Niels Bohr, and the answer is that everything is alive.

Poetry has a similar search, and its answer is not yet formulated, as it cannot understand nature except as a mirror of the spirit ...

Guy Davenport: from Olson, in The Geography of the Imagination, Forty Essays

They always are, for that is the way they like it.

Czesław Miłosz: from The Rising of the Sun, VII, Bells in Winter

Si j'ai du goût, ce n'est guères

Que pour la terre et les pierres.

This "taste for stone" is a theme in modern literature that emerges in the early days of Romantic writing and flows like a submerged river through practically all serious works in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It stems from the classical feeling that stone was a dead substance and therefore belonged to a separate realm of being. Hades, for instance, was stone, as was the dead moon. The firm Greek sense that stone does not grow distinguished it radically from things that do. And yet it was of mineral substance that everything was made: an organism was an interpenetration of matter and spirit.

Put the understanding another way: science and poetry from the Renaissance forward have been trying to discover what is alive and what isn't. In science the discovery spanned three centuries, from Gassendi to Niels Bohr, and the answer is that everything is alive.

Poetry has a similar search, and its answer is not yet formulated, as it cannot understand nature except as a mirror of the spirit ...

Guy Davenport: from Olson, in The Geography of the Imagination, Forty Essays

10.11.06

more about stones

When I first came to Sydney in 1981, I lived in Thomas Street, Chippendale, as it was then called, though properly it was Darlington and sometimes known as Redfern. Near one of the lost suburbs, Golden Grove, which now survives only as a street name. Anyway. A friend mentioned to me one day how you would sometimes find unusual stones around there, stones that looked as if they had been brought from elsewhere and placed, for some inscrutable reason, on a corner, next to a doorway, on a curb ... not long after he pointed this out to me, I found one of these stones in nearby Vine Street, not far from a big old sandstock curb that had the baleful letters K I L L inscribed in it, as if by some disaffected quarrying convict. I picked up this stone and kept it near me for many years, losing sight of it, unaccountably, when I left Pearl Beach to move back into the City a couple of years ago. It's probably still up there somewhere.

It was small enough to fit comfortably in the palm of my hand, irregularly shaped, very hard, and pitted all over. The upper surface was dark and rounded but, underneath, it was slightly concave and of a much paler colour, as if it had sat for a long time half in, half out of water. Someone I showed it to once told me that there are stones like that lying around about the blowhole at Kiama, on the South Coast. Maybe that's where it came from. Who brought it? Thomas Street is very close to The Block, where an urban Aboriginal community hangs on despite the many efforts from local and State government instrumentalities to re-locate them elsewhere. I used to wonder if these mysterious stones were an occult intervention in the psychogeography of the City but perhaps that's too romantic a notion.

And yet ... the other day, Friday, after I picked my sons up from Strathfield station, we were wandering back down Parnell Street to the car when I spotted another unusual stone, lying in the grass outside some double doors to somebody's garage or back yard. This, like the Kiama stone, is very hard and pitted all over, but it's quite a bit larger and the surface below the pits is a rust orange colour. It's much more regular in shape, indeed, it looks as if it has been worked to make a flattened ovoid, though exactly how you'd work a stone this hard is beyond me. It's just the way there's a slight ridge around the circumference when you lie it flat. This stone also fits comfortably in my hand, but only with my fingers and thumb curled around it. Feels good to heft. Would make an excellent grindstone and, if it is any kind of artefact, that's probably what it's for.

The impulse to pick up and carry away these stones is very strong but it's not unquestionable. If they are placed, shouldn't they be left there? Or, is it the case that they are placed in order that they be found and used again? I'm unlikely to grind with this stone but I will keep it and value it as long as it stays with me - and perhaps that's all a stone asks. Czeslaw Milosz says somewhere that stone is stone because it only wants to be stone. And yet ... who has not heard, at some estranged or estranging moment, the stones cry out to us?

It was small enough to fit comfortably in the palm of my hand, irregularly shaped, very hard, and pitted all over. The upper surface was dark and rounded but, underneath, it was slightly concave and of a much paler colour, as if it had sat for a long time half in, half out of water. Someone I showed it to once told me that there are stones like that lying around about the blowhole at Kiama, on the South Coast. Maybe that's where it came from. Who brought it? Thomas Street is very close to The Block, where an urban Aboriginal community hangs on despite the many efforts from local and State government instrumentalities to re-locate them elsewhere. I used to wonder if these mysterious stones were an occult intervention in the psychogeography of the City but perhaps that's too romantic a notion.

And yet ... the other day, Friday, after I picked my sons up from Strathfield station, we were wandering back down Parnell Street to the car when I spotted another unusual stone, lying in the grass outside some double doors to somebody's garage or back yard. This, like the Kiama stone, is very hard and pitted all over, but it's quite a bit larger and the surface below the pits is a rust orange colour. It's much more regular in shape, indeed, it looks as if it has been worked to make a flattened ovoid, though exactly how you'd work a stone this hard is beyond me. It's just the way there's a slight ridge around the circumference when you lie it flat. This stone also fits comfortably in my hand, but only with my fingers and thumb curled around it. Feels good to heft. Would make an excellent grindstone and, if it is any kind of artefact, that's probably what it's for.

The impulse to pick up and carry away these stones is very strong but it's not unquestionable. If they are placed, shouldn't they be left there? Or, is it the case that they are placed in order that they be found and used again? I'm unlikely to grind with this stone but I will keep it and value it as long as it stays with me - and perhaps that's all a stone asks. Czeslaw Milosz says somewhere that stone is stone because it only wants to be stone. And yet ... who has not heard, at some estranged or estranging moment, the stones cry out to us?

5.11.06

The Dogon Stones

Last year I filled out a coupon from a newspaper and subsequently received a free copy of the 11th edition of The Times Comprehensive Atlas of the World ... in the same act committing myself to buying four other books from the relevant source. Knew this was a mistake but wanted the Atlas ... love the Atlas. Took months of distraction to decide which among those available I would choose for my four purchases; meanwhile the junk mail quotient in my letter box increased exponentially. Because the original source misspelled my name, I can always tell when they've handed it on to someone else. All sorts of dubious people. Anyway, settled finally on a book for each for my sons - The Siege and Fall of Troy, Robert Graves' re-telling of The Iliad; The Wind in the Willows; - plus Brewer's Dictionary of Rogues, Villains, & Eccentrics (a disappointment); and The Life of Muhammad.

Have just started to read this last, by Ibn Ishaq, who was born in Medina about 85 years after the hijra of AD622 and died in Baghdad 66 years later. His inaugural biography survives only in a version edited by Ibn Hisham, who himself died about 60 years after Ibn Ishaq. The translation is by Hungarian Edward Rehatsek, made in Bombay and completed just before his own death in 1891. This voluminous work was, in its turn, edited by Michael Edwardes to make a slender, elegantly produced and written book of about 150 pages, first published in 1964. Somewhat to my surprise, I am enjoying it immensely. I love its mix of family and tribal history, folktale, hokum and divine revelation. Among the much I did not know about the subject is that the pre-Muslim Arabs of Mecca and Medina worshipped gods who were enshrined in stones. Nor did I know that the Kaba, which includes in itself a Black Stone that is thought to be a meteorite, predates Islam. You could perhaps say that the worship of stones has survived the advent of the Koran.

These disparate facts made me think of an encounter I was lucky enough to have, years ago now, with two remarkable stones from Africa. I knew, through my girlfriend at the time, a fellow called Ken de la Coeur. Ken was a Qantas steward who spent his time off in West Africa, buying all sorts of things that he would then bring back to Australia for resale. Anything from vast wooden canopied beds to tiny coloured beads made out of Venetian glass that had been melted down and then recast. Many of his things were rare and, since he had a good eye, all of them were beautiful. My girlfriend met him because she used to go into the shop he had on King Street, Newtown to trawl through that vast array. Ken didn't actually sell much, that wasn't really the point. Instead, he amassed a unique collection of West African art, mostly sourced from select dealers whom he'd got to know, and visited on his regular trips.

Ken loved the people of West Africa as much as their art, and it was probably from one of the men he met there that he contracted HIV. In time, he became too ill to keep the shop open, but he continued to run the business, such as it was, from his home in Redfern. After his last trip to West Africa, he held a soirée to which guests, mostly personal friends, were invited to come and view, perhaps purchase, his latest acquisitions. We were among the first to arrive at that event, and the last to leave. Very late in the evening, when there were just a few people still there, he brought out and unwrapped two stones that came, he said, from among the Dogon people of Mali. It is difficult for me describe the aura possessed by these two stones, one of which was male, one female. They were about the size of a small cantaloupe, ovid, reddish, one larger and darker than the other. I held them for a long time and did not want ever to let them go. Ken was asking a thousand dollars for the pair, far too much for me to consider buying them. In the end I did give them back and he re-wrapped them in their cloth and put them away.

Ken was from Melbourne. His family, whom I met at the wake, although they loved him, had never accepted that he was gay; and yet, when it came to his will, it turned out he left everything to them. Perhaps a worse tragedy was, he'd never catalogued his collection. His knowledge was extraordinary but most of what he knew wasn't written down. It was all in his head. You only had to point to something for Ken to tell you in detail its origin, provenance, significance and all sorts of other information about it. This knowledge went with him to his grave. As for the collection, the family gathered it up and shipped it to a warehouse in Melbourne. Later, I understand, it was broken up and sold. Most of it would have been represented only by the tiny cardboard tags, with Ken's fine calligraphy on them, that he would attach to his things. They would include a brief description, the location it came from, and a price - no more.

The stones, when I saw them, were not accompanied by any written description at all. They were probably, despite their size, of the kind worn in massive iron necklaces by Hogon or wise men; if so, they represented bones and were a source of power. I often wonder what happened to them, whether they were sold, or if they were thrown out or abandoned - after all, what use to anyone is an anonymous rock? Or perhaps not, perhaps the power that emanated from them meant that they have been acquired by someone who knows something of what they are. It is impossible to tell. I only had two things of Ken's: a small example of one of the afore-mentioned Venetian glass beads that he gave me, handed on recently to a dear friend for her fiftieth birthday. The other is a small bronze box, with three pairs of birds on the lid, facing each other, their beaks fused, that my girlfriend gave me. I do not know where the little card that came with it is now, though I may still have it. And yet there is a third: an indelible memory of the Dogon Stones.

Have just started to read this last, by Ibn Ishaq, who was born in Medina about 85 years after the hijra of AD622 and died in Baghdad 66 years later. His inaugural biography survives only in a version edited by Ibn Hisham, who himself died about 60 years after Ibn Ishaq. The translation is by Hungarian Edward Rehatsek, made in Bombay and completed just before his own death in 1891. This voluminous work was, in its turn, edited by Michael Edwardes to make a slender, elegantly produced and written book of about 150 pages, first published in 1964. Somewhat to my surprise, I am enjoying it immensely. I love its mix of family and tribal history, folktale, hokum and divine revelation. Among the much I did not know about the subject is that the pre-Muslim Arabs of Mecca and Medina worshipped gods who were enshrined in stones. Nor did I know that the Kaba, which includes in itself a Black Stone that is thought to be a meteorite, predates Islam. You could perhaps say that the worship of stones has survived the advent of the Koran.

These disparate facts made me think of an encounter I was lucky enough to have, years ago now, with two remarkable stones from Africa. I knew, through my girlfriend at the time, a fellow called Ken de la Coeur. Ken was a Qantas steward who spent his time off in West Africa, buying all sorts of things that he would then bring back to Australia for resale. Anything from vast wooden canopied beds to tiny coloured beads made out of Venetian glass that had been melted down and then recast. Many of his things were rare and, since he had a good eye, all of them were beautiful. My girlfriend met him because she used to go into the shop he had on King Street, Newtown to trawl through that vast array. Ken didn't actually sell much, that wasn't really the point. Instead, he amassed a unique collection of West African art, mostly sourced from select dealers whom he'd got to know, and visited on his regular trips.

Ken loved the people of West Africa as much as their art, and it was probably from one of the men he met there that he contracted HIV. In time, he became too ill to keep the shop open, but he continued to run the business, such as it was, from his home in Redfern. After his last trip to West Africa, he held a soirée to which guests, mostly personal friends, were invited to come and view, perhaps purchase, his latest acquisitions. We were among the first to arrive at that event, and the last to leave. Very late in the evening, when there were just a few people still there, he brought out and unwrapped two stones that came, he said, from among the Dogon people of Mali. It is difficult for me describe the aura possessed by these two stones, one of which was male, one female. They were about the size of a small cantaloupe, ovid, reddish, one larger and darker than the other. I held them for a long time and did not want ever to let them go. Ken was asking a thousand dollars for the pair, far too much for me to consider buying them. In the end I did give them back and he re-wrapped them in their cloth and put them away.

Ken was from Melbourne. His family, whom I met at the wake, although they loved him, had never accepted that he was gay; and yet, when it came to his will, it turned out he left everything to them. Perhaps a worse tragedy was, he'd never catalogued his collection. His knowledge was extraordinary but most of what he knew wasn't written down. It was all in his head. You only had to point to something for Ken to tell you in detail its origin, provenance, significance and all sorts of other information about it. This knowledge went with him to his grave. As for the collection, the family gathered it up and shipped it to a warehouse in Melbourne. Later, I understand, it was broken up and sold. Most of it would have been represented only by the tiny cardboard tags, with Ken's fine calligraphy on them, that he would attach to his things. They would include a brief description, the location it came from, and a price - no more.

The stones, when I saw them, were not accompanied by any written description at all. They were probably, despite their size, of the kind worn in massive iron necklaces by Hogon or wise men; if so, they represented bones and were a source of power. I often wonder what happened to them, whether they were sold, or if they were thrown out or abandoned - after all, what use to anyone is an anonymous rock? Or perhaps not, perhaps the power that emanated from them meant that they have been acquired by someone who knows something of what they are. It is impossible to tell. I only had two things of Ken's: a small example of one of the afore-mentioned Venetian glass beads that he gave me, handed on recently to a dear friend for her fiftieth birthday. The other is a small bronze box, with three pairs of birds on the lid, facing each other, their beaks fused, that my girlfriend gave me. I do not know where the little card that came with it is now, though I may still have it. And yet there is a third: an indelible memory of the Dogon Stones.

4.11.06

Diptych

One

Bruno’s Indian said something wise as I was leaving but, like so much of the wisdom that has come my way, I have forgotten it. He was a tall, slender young man, the foreman of the gang of Gujarati illegals who picked Bruno’s apples and pumpkins, but even his natural authority could not make them work on festival days, nor on the days when, for reasons that were obscure, they became spooked. I saw him in the rearview mirror, dressed in white, standing with my sister and her husband as I drove away from the sheds on the rich river flats down by the Tuki Tuki and then on out of the valley.

The back seat of the rental car was full of crisp red apples and my sister had given me some of the strong dope they grew in a favoured spot in the orchard. I was going to Wellington for an art opening, via south Hawkes Bay and the Wairarapa, intending to stop in a town of my youth to visit my father’s grave. I was happy to be free and untrammelled on the road, but throughout the morning and the early afternoon, a troubling image kept surfacing and floating before my mind’s eye: the bones of my father’s skull coming through the flesh down there in the earth where we'd buried him a couple of years before.

After I left Masterton I smoked a joint rolled previously which, while it did not banish the visage of the skull beneath the skin, did overlay it with intensely nostalgic images from my boyhood; so that when I crossed the bridge over the Waiohine, just north of Greytown, and saw kids swimming as I used to do in the swift green waters between the piles, I turned off the road and drove down the short track to the stony river beach where they had left their piles of clothes and their towels draped over gorse or broom bushes. But it was no longer possible for me to join them, so soon enough I reversed and turned about and bumped back up to the highway and on.

The graveyard is south of the town, with curiously shaped concrete wings over the gate that do not meet to make the arch they suggest. I had never explored it properly before, and was surprised to find it segregated: a small Jewish section and then the Catholics there on the right as you went up the drive, with a row of truncated macrocarpas on the left, behind which my father lay. Over the cattlestop and into the main part of the cemetery. I stopped the car near a small wooden shed built next to the boundary fence, climbed out, stretched. I was feeling strange already, otherwordly, perhaps trepidated, if that’s a word.

It was a still, partly cloudy afternoon, alternately bright and shadowed, and quiet except for the carolling of magpies from the tall pine trees up the back and the seemingly grief-stricken, intermittent cries of sheep from the surrounding paddocks. I walked over to the Sexton’s shed and peered through the dusty, spider-webbed window. Its floor was uneven, a turmoil of earth, as if someone had tried to excavate within. A broken shovel lay sideways in the dirt and there did not appear to be any back wall to it. That chaos of scumbled filth went forever. It was like a vision, not so much of hell, but of some brute vacuum beyond both heaven and hell. I felt myself being pulled into that vortex and it was an effort to drag myself away. The illusion so strong I went around the back to check if there was in fact a wall there …

A low hedge grew over the fence on that side of the graveyard and from in amongst its tangled greenery, its twiggy darkness, I could hear the rustling of some small animal or bird. There was another shed further along, I walked towards it as if impelled by the foreboding atmos around me. It was more miniature barn than shed, with double wooden doors, one of which was half open, the other secured with a bolt. The open side held more tools, a mower, fuel cans and so forth. I shot the bolt on the other door, it creaked open. Inside was a pile of yellow straw and laid on the straw, unaccountably, was the mummified body of a whippet or a small greyhound. The roar building in my ears became louder, I swayed, dizzy, faint. The body of the dog filled me with horror, the rustling in the hedgerow likewise. I closed the door and stumbled away.

Up the back of the graveyard, under the huge, raggedy pines, is a rectangular field in which are a couple of dozen massive, elaborate, nineteenth century graves all set on a diagonal with respect to the parameters of the enclosure. As I walked into that field, the sun went behind a cloud, the magpies flew up, with loud cries, out of the pines and away. The roaring in my ears crescendoed and I seemed to hear, above or below or amongst it, the grumbling voices of the dead town fathers and mothers buried here, a stern and heartless rehearsal of the Anglican pieties that ruled the town. The graves were disposed, I thought, on a ley line that stretched, past the brown hills to the northeast, over the manifold ocean, all the way back to some dim, occulted village in England.

No! I said, or shouted, though not out loud. No, no, no! I would not submit to their dread authority, I was not subject to their haunting, they could not own my soul the way they thought they owned the soul of the town. Their dead hand could fall where it would, but not on my sleeve, nor my shoulder, not on your life. I walked among the old graves, reading the names, muttering my refusals, and heard the ancient voices diminish to a murmur of discontent then die away into the dark and bright light of the afternoon.

Whatever it was, or had been, was over. I left that baleful field and made my way back through the military section to where my father lay. When we buried him I brought two stones for his grave, one from each of the two rivers that run through the town where I was born. The round one, like a skull, that I found at the bend in the Mangawhero where we used to go swimming, was set in concrete at the head of the grave, but the wide flat footstone I pulled out of the Mangateitei on the slopes of the mountain was missing. I stood where it should have been and spoke a few words out loud to him; then was quiet. The decay of his body no longer worried me. I even felt a kind of peace descend, neither profound nor momentous, but ordinary, mortal. In that silence, that peace, I heard the ticking of his watch on my wrist.

Two

The morning after the opening, I hit the road again, driving back to Auckland via Taranaki. I had someone to see, a rich art collector, in New Plymouth. I stayed the night in a motel at Waitara, then continued on up Highway 3, which runs along that wild coast as far as Mokau. I smoked another joint of my sister’s strong dope as I left town which, again, might explain the experience I was about to have. On the other hand, things like this have happened to me, unpredictably, when I’ve been unstoned, or stone cold sober.

I was barrelling down a wide empty sweep of highway towards a river bridge when I felt a sudden urge to stop. I drove over the bridge and turned off to the right, onto an obscure country dirt road. No, this wasn’t it. I turned the car around, went back, re-crossed the bridge and took another road that ran along the side of the river towards the sea. There was a carpark and picnic area about a kilometre along. I left the car there, intending to walk out along the tidal riverbed to the sea.

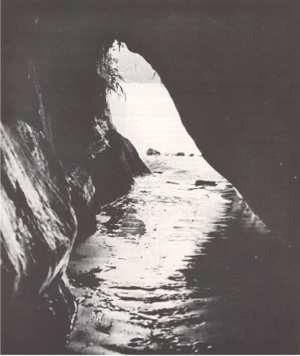

It was mid morning. A fine day. The tide was out. I took off my shoes, left them where I could easily find them again and set off across mudflats towards a high ridge of black iron sand, glinting with mica. It squeaked as my feet sank into it, leaving behind sighing holes that soon filled up with sand trickles. Past this ridge I could see a curiously truncated headland made of yellowish-brown sandstone, capped with tough grass. Fragmentary islands of the same rock out in the sea. I thought if I could get around this promontory I might find an ocean beach beyond.

The walk was longer than I expected, and as I neared the head of the headland I saw that it was riven through by a cave that might or might not go all the way to the other side. The dark aperture of the cave mouth seemed forbidding or forbidden so I plodded on, round the point and out onto a wide beach that stretched away south for kilometres. There before me, at the back of the high tide line, stood a strange, weather-beaten structure, shiny and white as bones. It resembled one of those stages that were made to lay out the bodies of the dead until all the flesh had gone from the bones, which would then be cleaned and gathered together and hidden away in some cave.

It even looked, from a distance, as if there might be bones upon it, but as I moved closer I saw it was not so: just a platform made out of driftwood, about a metre tall and two metres broad. Lashed together with baling twine that was already pale and fraying. What on earth was it for? Who had made it? Why? It was as foreboding as it was mysterious. I sat down next to it and wondered; then, since the day was warm and there was no-one around, took off all my clothes and went down into the surf.

A perfect set, seven waves, rolled in as I walked out, and I caught the last of them and shot shoreward in a hiss and bubble and surge of white water. Beautiful. Out again I went, and in on another perfect wave. And again, and again. I was as if drunk with exaltation and it wasn’t until, shivering with cold, I finally, regretfully, left the water and went back up to where my clothes were that I realised the tide was coming in—fast. The sea was already lapping at the base of the stubby yellow-brown headland where, moments ago, as it seemed, I’d walked across crunchy dry black sand.

In a panic now, I threw on my clothes and started back. It was too late to return as I had come, the only way was via the cave which did in fact go right through the headland. The premonitory fear I’d felt before was still with me but the urge to reach the other side before the tidal river became impassable was stronger. Sea water was sliding into the cave mouth as I entered, starting to run. So it was that the markings on the cave walls, the ancestral figures with triangular heads and slanted eyes, the chevrons and the double spirals, and, upright along the walls, the many stylised feet, three and four and six and seven-toed, the toes made of holes drilled in the rock, passed in the blur. And yet I seemed to hear a hiss of voices as I ran, a jostling, archaic, sibilant chorus which might just have been the waves of the sea, advancing.

It was hard to move at speed across that long black reach of glittering sand, and exhausting too, and by the time I was over it, the tidal river was knee deep; when I’d waded back to where my shoes were, under a flax bush on a clod of earthy bank, my trousers were wet to the thighs and my heart was going like billy-o. But that was alright; I was safe.

It wasn’t until I got to Auckland and looked at the catalogue of the art opening I’d attended in Wellington, that I realised where I’d been: Tongaporutu, Tony Fomison writes in a 1980 essay reprinted towards the back of What shall we tell them?, is the largest rock art site in Taranaki. Here wayfarers, or war parties, paused on the main Waikato to Taranaki track. Here, perhaps, the ceremony called uruuruwhenua was performed. Fomison quotes James Cowan: If you wish to avoid heavy rain or other obstruction or inconvenience on your day’s journey, you must pay due respect to Tokahaere (a ‘walking rock’ in the King Country) by pulling a handful of fern or manuka and laying it at his foot, reciting as you do an ancient prayer to the spirit of the rock …

I did not of course have the time for such a ceremony, even if I'd known what it was. All I had was a glimpse of an antique mystery, a once sacred place that is now a curiosity and will soon disappear under the inexorable rise of the ocean, as so many other sites that existed along that coast already have done. Yet I drove away over the bridge and up the wide sweet highway on the other side with a clean feeling, as if the sea, though not perhaps the cave, had scoured my skin of the accretion of those half-formed, half-unadmitted residues of the flotsam we pick up as we live through our days. As if I had been, momentarily, serendipitously, reborn.

Bruno’s Indian said something wise as I was leaving but, like so much of the wisdom that has come my way, I have forgotten it. He was a tall, slender young man, the foreman of the gang of Gujarati illegals who picked Bruno’s apples and pumpkins, but even his natural authority could not make them work on festival days, nor on the days when, for reasons that were obscure, they became spooked. I saw him in the rearview mirror, dressed in white, standing with my sister and her husband as I drove away from the sheds on the rich river flats down by the Tuki Tuki and then on out of the valley.

The back seat of the rental car was full of crisp red apples and my sister had given me some of the strong dope they grew in a favoured spot in the orchard. I was going to Wellington for an art opening, via south Hawkes Bay and the Wairarapa, intending to stop in a town of my youth to visit my father’s grave. I was happy to be free and untrammelled on the road, but throughout the morning and the early afternoon, a troubling image kept surfacing and floating before my mind’s eye: the bones of my father’s skull coming through the flesh down there in the earth where we'd buried him a couple of years before.

After I left Masterton I smoked a joint rolled previously which, while it did not banish the visage of the skull beneath the skin, did overlay it with intensely nostalgic images from my boyhood; so that when I crossed the bridge over the Waiohine, just north of Greytown, and saw kids swimming as I used to do in the swift green waters between the piles, I turned off the road and drove down the short track to the stony river beach where they had left their piles of clothes and their towels draped over gorse or broom bushes. But it was no longer possible for me to join them, so soon enough I reversed and turned about and bumped back up to the highway and on.

The graveyard is south of the town, with curiously shaped concrete wings over the gate that do not meet to make the arch they suggest. I had never explored it properly before, and was surprised to find it segregated: a small Jewish section and then the Catholics there on the right as you went up the drive, with a row of truncated macrocarpas on the left, behind which my father lay. Over the cattlestop and into the main part of the cemetery. I stopped the car near a small wooden shed built next to the boundary fence, climbed out, stretched. I was feeling strange already, otherwordly, perhaps trepidated, if that’s a word.

It was a still, partly cloudy afternoon, alternately bright and shadowed, and quiet except for the carolling of magpies from the tall pine trees up the back and the seemingly grief-stricken, intermittent cries of sheep from the surrounding paddocks. I walked over to the Sexton’s shed and peered through the dusty, spider-webbed window. Its floor was uneven, a turmoil of earth, as if someone had tried to excavate within. A broken shovel lay sideways in the dirt and there did not appear to be any back wall to it. That chaos of scumbled filth went forever. It was like a vision, not so much of hell, but of some brute vacuum beyond both heaven and hell. I felt myself being pulled into that vortex and it was an effort to drag myself away. The illusion so strong I went around the back to check if there was in fact a wall there …

A low hedge grew over the fence on that side of the graveyard and from in amongst its tangled greenery, its twiggy darkness, I could hear the rustling of some small animal or bird. There was another shed further along, I walked towards it as if impelled by the foreboding atmos around me. It was more miniature barn than shed, with double wooden doors, one of which was half open, the other secured with a bolt. The open side held more tools, a mower, fuel cans and so forth. I shot the bolt on the other door, it creaked open. Inside was a pile of yellow straw and laid on the straw, unaccountably, was the mummified body of a whippet or a small greyhound. The roar building in my ears became louder, I swayed, dizzy, faint. The body of the dog filled me with horror, the rustling in the hedgerow likewise. I closed the door and stumbled away.

Up the back of the graveyard, under the huge, raggedy pines, is a rectangular field in which are a couple of dozen massive, elaborate, nineteenth century graves all set on a diagonal with respect to the parameters of the enclosure. As I walked into that field, the sun went behind a cloud, the magpies flew up, with loud cries, out of the pines and away. The roaring in my ears crescendoed and I seemed to hear, above or below or amongst it, the grumbling voices of the dead town fathers and mothers buried here, a stern and heartless rehearsal of the Anglican pieties that ruled the town. The graves were disposed, I thought, on a ley line that stretched, past the brown hills to the northeast, over the manifold ocean, all the way back to some dim, occulted village in England.

No! I said, or shouted, though not out loud. No, no, no! I would not submit to their dread authority, I was not subject to their haunting, they could not own my soul the way they thought they owned the soul of the town. Their dead hand could fall where it would, but not on my sleeve, nor my shoulder, not on your life. I walked among the old graves, reading the names, muttering my refusals, and heard the ancient voices diminish to a murmur of discontent then die away into the dark and bright light of the afternoon.

Whatever it was, or had been, was over. I left that baleful field and made my way back through the military section to where my father lay. When we buried him I brought two stones for his grave, one from each of the two rivers that run through the town where I was born. The round one, like a skull, that I found at the bend in the Mangawhero where we used to go swimming, was set in concrete at the head of the grave, but the wide flat footstone I pulled out of the Mangateitei on the slopes of the mountain was missing. I stood where it should have been and spoke a few words out loud to him; then was quiet. The decay of his body no longer worried me. I even felt a kind of peace descend, neither profound nor momentous, but ordinary, mortal. In that silence, that peace, I heard the ticking of his watch on my wrist.

Two

The morning after the opening, I hit the road again, driving back to Auckland via Taranaki. I had someone to see, a rich art collector, in New Plymouth. I stayed the night in a motel at Waitara, then continued on up Highway 3, which runs along that wild coast as far as Mokau. I smoked another joint of my sister’s strong dope as I left town which, again, might explain the experience I was about to have. On the other hand, things like this have happened to me, unpredictably, when I’ve been unstoned, or stone cold sober.

I was barrelling down a wide empty sweep of highway towards a river bridge when I felt a sudden urge to stop. I drove over the bridge and turned off to the right, onto an obscure country dirt road. No, this wasn’t it. I turned the car around, went back, re-crossed the bridge and took another road that ran along the side of the river towards the sea. There was a carpark and picnic area about a kilometre along. I left the car there, intending to walk out along the tidal riverbed to the sea.

It was mid morning. A fine day. The tide was out. I took off my shoes, left them where I could easily find them again and set off across mudflats towards a high ridge of black iron sand, glinting with mica. It squeaked as my feet sank into it, leaving behind sighing holes that soon filled up with sand trickles. Past this ridge I could see a curiously truncated headland made of yellowish-brown sandstone, capped with tough grass. Fragmentary islands of the same rock out in the sea. I thought if I could get around this promontory I might find an ocean beach beyond.

The walk was longer than I expected, and as I neared the head of the headland I saw that it was riven through by a cave that might or might not go all the way to the other side. The dark aperture of the cave mouth seemed forbidding or forbidden so I plodded on, round the point and out onto a wide beach that stretched away south for kilometres. There before me, at the back of the high tide line, stood a strange, weather-beaten structure, shiny and white as bones. It resembled one of those stages that were made to lay out the bodies of the dead until all the flesh had gone from the bones, which would then be cleaned and gathered together and hidden away in some cave.

It even looked, from a distance, as if there might be bones upon it, but as I moved closer I saw it was not so: just a platform made out of driftwood, about a metre tall and two metres broad. Lashed together with baling twine that was already pale and fraying. What on earth was it for? Who had made it? Why? It was as foreboding as it was mysterious. I sat down next to it and wondered; then, since the day was warm and there was no-one around, took off all my clothes and went down into the surf.

A perfect set, seven waves, rolled in as I walked out, and I caught the last of them and shot shoreward in a hiss and bubble and surge of white water. Beautiful. Out again I went, and in on another perfect wave. And again, and again. I was as if drunk with exaltation and it wasn’t until, shivering with cold, I finally, regretfully, left the water and went back up to where my clothes were that I realised the tide was coming in—fast. The sea was already lapping at the base of the stubby yellow-brown headland where, moments ago, as it seemed, I’d walked across crunchy dry black sand.

In a panic now, I threw on my clothes and started back. It was too late to return as I had come, the only way was via the cave which did in fact go right through the headland. The premonitory fear I’d felt before was still with me but the urge to reach the other side before the tidal river became impassable was stronger. Sea water was sliding into the cave mouth as I entered, starting to run. So it was that the markings on the cave walls, the ancestral figures with triangular heads and slanted eyes, the chevrons and the double spirals, and, upright along the walls, the many stylised feet, three and four and six and seven-toed, the toes made of holes drilled in the rock, passed in the blur. And yet I seemed to hear a hiss of voices as I ran, a jostling, archaic, sibilant chorus which might just have been the waves of the sea, advancing.

It was hard to move at speed across that long black reach of glittering sand, and exhausting too, and by the time I was over it, the tidal river was knee deep; when I’d waded back to where my shoes were, under a flax bush on a clod of earthy bank, my trousers were wet to the thighs and my heart was going like billy-o. But that was alright; I was safe.

It wasn’t until I got to Auckland and looked at the catalogue of the art opening I’d attended in Wellington, that I realised where I’d been: Tongaporutu, Tony Fomison writes in a 1980 essay reprinted towards the back of What shall we tell them?, is the largest rock art site in Taranaki. Here wayfarers, or war parties, paused on the main Waikato to Taranaki track. Here, perhaps, the ceremony called uruuruwhenua was performed. Fomison quotes James Cowan: If you wish to avoid heavy rain or other obstruction or inconvenience on your day’s journey, you must pay due respect to Tokahaere (a ‘walking rock’ in the King Country) by pulling a handful of fern or manuka and laying it at his foot, reciting as you do an ancient prayer to the spirit of the rock …

I did not of course have the time for such a ceremony, even if I'd known what it was. All I had was a glimpse of an antique mystery, a once sacred place that is now a curiosity and will soon disappear under the inexorable rise of the ocean, as so many other sites that existed along that coast already have done. Yet I drove away over the bridge and up the wide sweet highway on the other side with a clean feeling, as if the sea, though not perhaps the cave, had scoured my skin of the accretion of those half-formed, half-unadmitted residues of the flotsam we pick up as we live through our days. As if I had been, momentarily, serendipitously, reborn.

2.11.06

Lost Things

Started this blog a few months ago because I'd written something that didn't seem to belong anywhere else, so I pulled up this site and put it here. One other similar piece followed ... then nothing. When I thought to re-start the site, I didn't understand what these two posts meant, so deleted them. A fresh start, perhaps. Now, of course, I want to have another look at them but they're gone forever - hadn't configured the options so that my posts were emailed to me. They have joined the File of Lost Things.

I imagine everyone who writes has such a File, more or less extensive. Mine is quite large, mainly for technical reasons. My first computer was an Amstrad and, although I obsessively backed everything up to disk, those disks were a different size to the standard floppy and can only be read on the now obsolete Amstrad. Some years ago I tracked down someone who said he could, for a fee, translate them to Word. I sent him money and the disks but, despite a series of phone calls, he never reciprocated. The last time I rang his number it had been disconnected. There's not much I regret from that cache, the only thing I'd like to look at again is a screenplay I wrote, very quickly, around my travels in coup-afflicted Fiji in 1988.

After the Amstrad died, I bought a small Apple Mac laptop. It was stolen in a house break-in at Pearl Beach in 1998, just after I had finished, printed and sent to my publisher the book I wrote about artist Philip Clairmont. If the theft had happened two weeks earlier I would have lost the book - so, although it was a bitch, I felt the timing was in one way fortunate. From that machine I mourn the loss of some personal communications from people who have since died, and two short prose pieces that I was quite proud of but for some reason never printed out. They represented the beginning of an involvement with a form I have come love, though I don't know what it is called.

Anyway, I've been thinking about those two short pieces lately and have now decided to attempt to reconstitute them. They will not be as they were, but at least they will be. I'll try and rewrite them over the weekend and, if I like the results, will post them here. As for the lost two first White City posts ... I'll let them go to god, who was, I seem to remember, their subject.

I imagine everyone who writes has such a File, more or less extensive. Mine is quite large, mainly for technical reasons. My first computer was an Amstrad and, although I obsessively backed everything up to disk, those disks were a different size to the standard floppy and can only be read on the now obsolete Amstrad. Some years ago I tracked down someone who said he could, for a fee, translate them to Word. I sent him money and the disks but, despite a series of phone calls, he never reciprocated. The last time I rang his number it had been disconnected. There's not much I regret from that cache, the only thing I'd like to look at again is a screenplay I wrote, very quickly, around my travels in coup-afflicted Fiji in 1988.

After the Amstrad died, I bought a small Apple Mac laptop. It was stolen in a house break-in at Pearl Beach in 1998, just after I had finished, printed and sent to my publisher the book I wrote about artist Philip Clairmont. If the theft had happened two weeks earlier I would have lost the book - so, although it was a bitch, I felt the timing was in one way fortunate. From that machine I mourn the loss of some personal communications from people who have since died, and two short prose pieces that I was quite proud of but for some reason never printed out. They represented the beginning of an involvement with a form I have come love, though I don't know what it is called.

Anyway, I've been thinking about those two short pieces lately and have now decided to attempt to reconstitute them. They will not be as they were, but at least they will be. I'll try and rewrite them over the weekend and, if I like the results, will post them here. As for the lost two first White City posts ... I'll let them go to god, who was, I seem to remember, their subject.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Blog Archive

other places

- derives

- luca antara

- arroyo chamisa

- as is

- australian literary resources

- bibliOdyssey

- blazevox

- camera shy

- charlotte street

- cipango

- conchology

- david baptiste chirot

- deoxyribonucleic hyperdimension

- doug allen

- enemy of the republic

- equanimity

- error-404

- fait accompli

- gamma ways

- grapez

- growing nation

- hoopla!

- humming to itself

- in the works

- institute of broken and reduced languages

- irish poetry

- ironic points of light

- isola de rifiuti

- ivy is here

- jacket

- k-punk

- laputan logic

- long sunday

- maelstrom

- miss wanda

- mod style

- morgana le fay

- mountain 7

- narcissusworks

- navel orange

- negative wingspan

- never neutral

- nietzsche's wife

- noel peters' eredia

- nonlinear poetry

- notes from a fellow traveler

- nzepc

- nzepc dig

- okir

- olson

- one million footnotes

- outlasting moths

- outside my window

- p-ramblings

- pedestrian happiness

- pelican dreaming

- peyoetry

- poeta en san francisco

- poetry off the page

- poetry scorecard

- press flat

- pseudopodium

- quick little splinter

- quiet desperation

- raindancers map of memories

- rb sprague studio work

- reading & writing

- really bad movies

- river's blue elephants

- ruby street

- series magritte

- shanna compton

- silliman

- slave2love's rants

- smelt money

- soluble census

- swarf

- tex files

- the blind chatelaine’s poker poetics

- the deletions

- the found diary of avery alexander myer

- the imaginary museum

- the night jar

- the surging waves

- this space

- trees lounge

- ubuweb

- unlabeled

- vaults of erowid

- walleah press

- young chang